When a pregnant person takes a medication, it doesn’t just stay in their body. It travels through the bloodstream and reaches the placenta - the organ that connects mother and baby. But here’s the thing: the placenta isn’t a wall. It’s more like a smart filter. Some drugs slip right through. Others get blocked. And some even get pushed back out. What happens next can affect the developing fetus in ways that aren’t always obvious - or predictable.

How the Placenta Really Works

The placenta weighs about half a kilogram at full term, is roughly the size of a dinner plate, and has a surface area of 15 square meters - that’s bigger than a small bedroom. All that tissue exists for one purpose: to let nutrients in and waste out. But it also lets drugs through. And not all drugs behave the same.

Small molecules under 500 daltons cross easily. Think ethanol (alcohol) or nicotine. Both slip through the placental barrier like water through a sieve. Within an hour, fetal blood levels match maternal levels. That’s why drinking or smoking during pregnancy carries such clear risks.

But bigger molecules? Insulin, for example, is over 5,800 daltons. It barely crosses. Less than 0.1% of the mother’s insulin reaches the fetus. That’s why insulin is often safe to use in gestational diabetes - it doesn’t cross much. But drugs like methadone? At 237 daltons, it slips through easily. Fetal concentrations reach 65-75% of the mother’s level. That’s why babies born to mothers on methadone often go through withdrawal.

The Hidden Gatekeepers: Transporter Proteins

It’s not just about size or fat-solubility. The placenta has its own built-in security system. Two major transporter proteins - P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) - act like bouncers at a club. They recognize certain drugs and actively pump them back into the mother’s blood, away from the fetus.

Take HIV medications. Lopinavir, saquinavir, and indinavir are all designed to fight the virus. But they’re also targets for P-gp. In lab studies, when researchers blocked P-gp, fetal exposure to these drugs jumped by up to 2.3 times. That’s huge. In real life, this means a drug that seems safe because it doesn’t cross much might suddenly become risky if taken with another medication that blocks these transporters.

And it’s not just HIV drugs. Methadone, buprenorphine, and morphine? They don’t just cross the placenta - they interfere with the placenta’s own defense system. Studies show they block the transport of chemotherapy drugs like paclitaxel. That’s a double-edged sword: it might protect the fetus from some drugs, but it could also make other drugs more dangerous by disrupting normal placental function.

Why Timing Matters More Than You Think

Most people think the placenta works the same way all through pregnancy. It doesn’t. In the first trimester, the barrier is looser. Tight junctions between cells aren’t fully formed. Efflux transporters like P-gp and BCRP are still developing. That means drugs cross more easily - and the fetus is far more vulnerable.

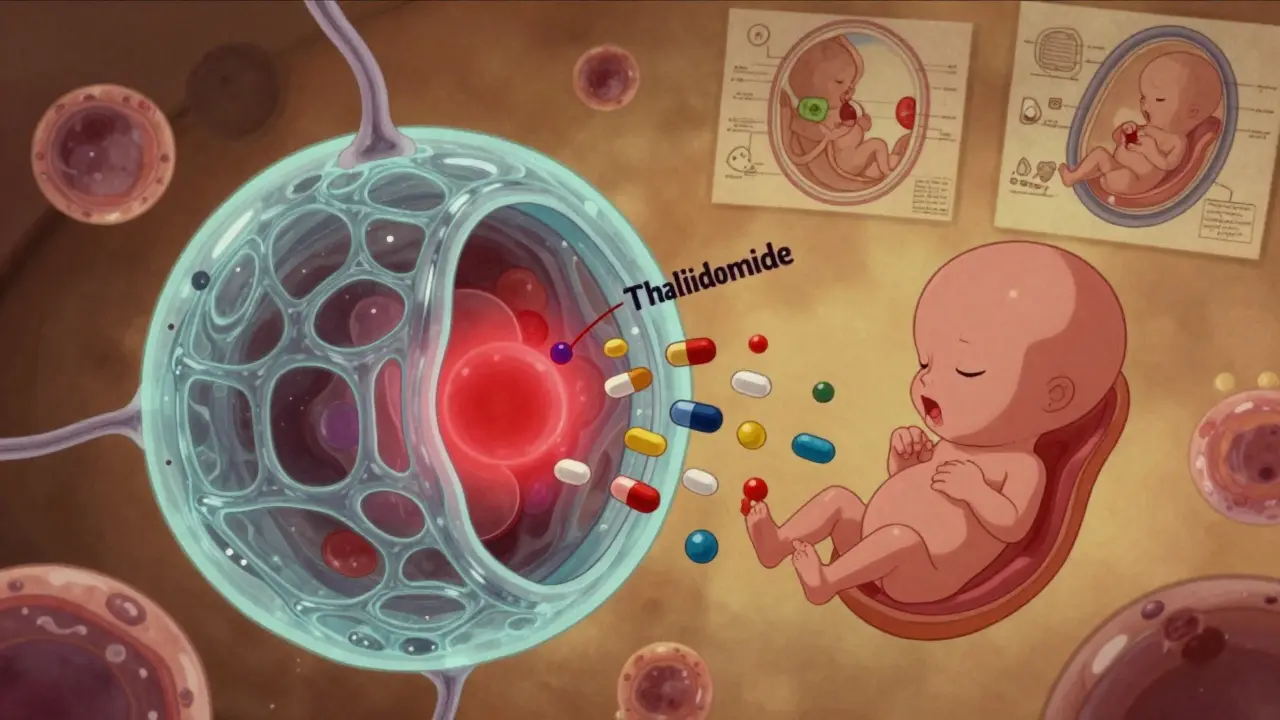

That’s why birth defects from drugs like thalidomide happened in the early weeks of pregnancy. The baby’s organs were forming. The placenta couldn’t stop the drug. Today, we know that the window for major structural damage is narrow - between weeks 3 and 8. But even after that, drugs can affect brain development, organ function, and growth.

By the third trimester, the placenta tightens up. Transporters become more active. But here’s the catch: we don’t test drugs on first-trimester placentas enough. Most studies use placentas from full-term births. That means we’re guessing how drugs behave in the most critical window. As one researcher put it: “We’re using a map of the destination to navigate the start of the journey.”

Real-World Examples: What Crosses - and What Doesn’t

- SSRIs (like sertraline): Cross readily. Cord-to-maternal ratios of 0.8 to 1.0 mean fetal levels are nearly equal to the mother’s. About 30% of babies exposed to these drugs in the third trimester show temporary symptoms like jitteriness, feeding trouble, or breathing issues after birth.

- Valproic acid: Used for seizures. Crosses easily. Linked to a 10-11% risk of major birth defects - including neural tube defects and facial malformations. That’s 3-5 times higher than the general population.

- Phenobarbital: Also used for seizures. Molecular weight 232. Crosses almost completely. Fetal levels match maternal levels. Used for decades, but still carries risks for neurodevelopment.

- Digoxin: Used for heart conditions. Despite being a small molecule, it crosses poorly. Why? It’s not about size - it’s about the placenta’s specific transporters. Digoxin doesn’t trigger the efflux pumps, so it moves slowly. And even when you give the mother drugs like quinidine or verapamil (which block other transporters), digoxin transfer doesn’t change. It’s a rare case of predictable behavior.

- Warfarin: Even though it’s small and fat-soluble, over 99% of it sticks to proteins in the blood. Only the tiny unbound fraction crosses. That’s why warfarin is sometimes used in pregnancy - but only with extreme caution. It still carries a risk of fetal bleeding and bone malformations.

What We’re Still Missing

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: we don’t know how most drugs affect the fetus. A 2013 study found that 45% of prescription drugs used during pregnancy have no reliable data on placental transfer. That’s not because doctors are careless. It’s because testing is hard.

Animal studies don’t translate well. Mouse placentas are structurally different - they’re more permeable. So a drug that looks safe in rats might be dangerous in humans. And we can’t ethically test drugs on pregnant women in controlled trials.

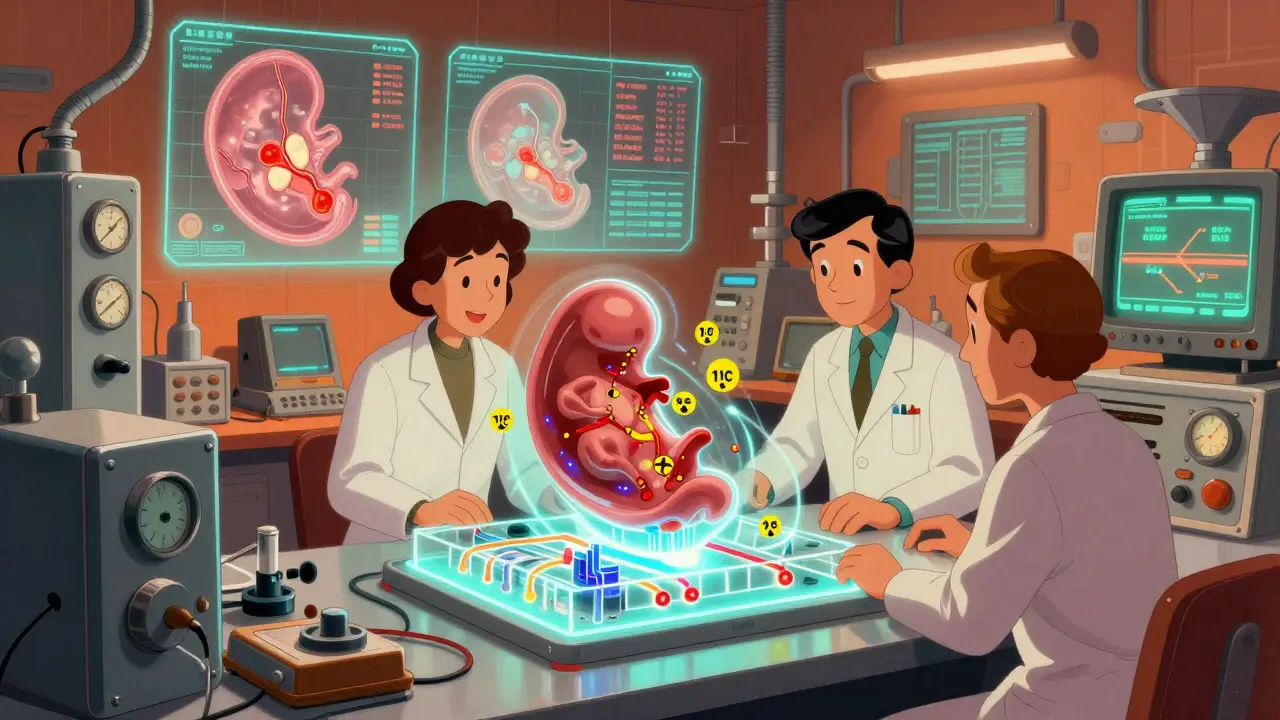

That’s why new tools are being developed. Placenta-on-a-chip devices now mimic the real organ’s structure and function. They’ve shown 92% accuracy in predicting drug transfer compared to actual human tissue. Scientists are also using radioactive tracers like 11C to watch drug movement in real time - no surgery needed.

And then there’s the future: nanodrugs. Tiny particles designed to deliver medicine directly to the fetus. Sounds promising - until you realize we don’t know if nanoparticles get stuck in the placenta. Could they cause inflammation? Damage cells? We’re building the plane while we’re still figuring out how to fly it.

What Should You Do?

If you’re pregnant and taking medication - whether it’s for depression, epilepsy, diabetes, or chronic pain - don’t stop cold turkey. Talk to your doctor. Ask:

- Is this drug known to cross the placenta?

- Are there safer alternatives?

- Should I get my blood levels checked?

- Is this drug being used at the lowest effective dose?

For some conditions - like epilepsy or severe depression - the risk of stopping medication is higher than the risk of continuing it. But that decision needs to be based on real data, not guesswork.

The FDA now requires drug manufacturers to include placental transfer data in new drug applications. That’s progress. But it’s still not enough. Many drugs already on the market were approved before these rules existed. That’s why therapeutic drug monitoring - checking blood levels - matters more than ever.

There’s no perfect answer. But there is a better way: informed choices. Understanding how drugs move - and how they don’t - is the first step to protecting both mother and baby.

Can all medications cross the placenta?

No. Not all medications cross the placenta equally. Small, fat-soluble drugs like alcohol and nicotine cross easily. Large molecules like insulin barely cross. Some drugs, like certain HIV medications and chemotherapy agents, are actively pushed back by placental transporter proteins like P-glycoprotein. Even among drugs that cross, the amount varies widely - from less than 1% to nearly 100% of the mother’s concentration.

Are there drugs that are considered safe during pregnancy?

There’s no universal list of "safe" drugs. What’s safe for one person might not be for another. Some drugs, like folic acid, prenatal vitamins, and certain antibiotics (like penicillin), have strong safety records. Others, like insulin for diabetes or certain antiseizure medications, are used because the benefits outweigh the risks. The key is individualized care - not blanket approval. Always consult a provider who knows your medical history.

Why do some drugs affect the fetus more in early pregnancy?

In the first trimester, the placenta is still developing. Its protective transporters - like P-gp and BCRP - aren’t fully active yet. Also, the baby’s organs are forming. A drug that interferes with cell division or organ growth during this time can cause structural birth defects. Later in pregnancy, the placenta is more mature and better at filtering, but the fetus is still vulnerable to growth issues and neurological effects.

Do over-the-counter drugs cross the placenta too?

Yes. Many OTC drugs - including pain relievers like ibuprofen and acetaminophen, cold medicines, and even some herbal supplements - cross the placenta. Ibuprofen, for example, crosses easily and can reduce amniotic fluid if taken late in pregnancy. Acetaminophen is generally considered low-risk, but recent studies suggest high or prolonged use may affect fetal development. Just because it’s available without a prescription doesn’t mean it’s risk-free.

What’s being done to improve our understanding of placental drug transfer?

Researchers are using advanced tools like placenta-on-a-chip devices, real-time imaging with radioactive tracers, and human placental tissue models to study drug movement more accurately. Regulatory agencies now require placental transfer data for new drugs. The NIH’s Human Placenta Project has funded over $84 million in research since 2014. These efforts aim to replace unreliable animal data with human-based science - so future pregnancies can be safer.

John McDonald

February 8, 2026 AT 12:15Man, I never realized how complex the placenta really is. I always thought it was just a filter, but it's more like a bouncer with a PhD. The whole P-gp and BCRP thing? Wild. I had no idea drugs like methadone could mess with chemo transporters. Makes you think twice before popping a pill ‘cause it’s ‘safe.’

Chelsea Cook

February 10, 2026 AT 11:35So let me get this straight - we’re giving pregnant people drugs based on data from placentas that are 30 weeks old… while the most critical window is at 6 weeks? That’s not science. That’s gambling with a baby’s brain. And yet we still don’t have enough human data? I’m not mad. I’m just disappointed.

Andy Cortez

February 12, 2026 AT 10:59lol so u mean to tell me that my ex’s mom took ibuprofen at 8 weeks n the baby was fine?? 😂 i mean like… if u believe all this science then why is there like 1000 ppl who took benadryl n their kids are normal??

also i heard a doc say once that ‘the placenta is just a filter’ so like… is this whole post just overcomplicating it??

also i think the FDA is lying. they just wanna make more money off new drug labels. #conspiracy

Joshua Smith

February 14, 2026 AT 06:53This is one of the clearest explanations I’ve read on placental transfer. The breakdown of molecular weight vs. transporter proteins makes so much sense. I’ve been on sertraline during both pregnancies and always wondered why my OB didn’t just say ‘it crosses, but here’s what we know.’ This level of detail is what patients need.

Also, the part about digoxin? That’s wild. A small molecule that barely crosses because it doesn’t trigger the pumps? Nature’s got its own logic.

Jessica Klaar

February 15, 2026 AT 18:38As someone from a culture where herbal teas are used for everything during pregnancy - ginger for nausea, turmeric for inflammation - I’m glad this post mentioned OTC stuff. My aunt swore by ‘pennyroyal tea’ to ‘cleanse’ the womb. No one told her it’s toxic. We need more culturally aware conversations around this. Science doesn’t live in a lab. It lives in kitchens, in markets, in grandmas’ advice.

And yeah, we need better data. But we also need to stop shaming people for using what they’ve always trusted. Education, not fear.

PAUL MCQUEEN

February 15, 2026 AT 22:40Ugh. Another ‘science is complicated’ article. Can we just say: if it’s not FDA-approved for pregnancy, don’t take it? Done. No need for 2000 words on transporter proteins. My OB says ‘avoid all meds unless absolutely necessary.’ That’s all I need to know.

Also, why are we even discussing this? Just eat clean, take prenatal vitamins, and stop worrying. You’re overthinking it.

glenn mendoza

February 17, 2026 AT 06:00It is with profound respect for the intricate biological mechanisms of human gestation that I acknowledge the monumental significance of the placental barrier as a dynamic, regulative interface. The expression of efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein and BCRP represents an evolutionary adaptation of extraordinary sophistication, and the current state of pharmacokinetic research remains woefully inadequate in capturing its full complexity.

I commend the authors for their rigorous methodology and urge the medical community to prioritize human placental tissue modeling over animal extrapolation. The ethical imperative is clear: we must act with precision, not presumption.

Patrick Jarillon

February 18, 2026 AT 04:51Y’all know the government and pharma companies have been hiding the truth for decades. The placenta doesn’t ‘filter’ - it’s a bioweapon designed to protect the fetus from corporate drugs. They *want* you to think it’s ‘smart’ so you keep taking SSRIs and painkillers. The real danger? The nanoparticles. They’re already in your vaccines. They get stuck in the placenta and cause autism. Ask your doctor if they’ve read the 2018 WHO internal memo.

Also, insulin? It’s not safe. It’s a synthetic hormone that disrupts fetal epigenetics. I’ve got 17 research papers. Want them?

Randy Harkins

February 19, 2026 AT 06:56This is why I love science. 🙌 So many people think ‘natural’ means safe, but the truth is way more interesting - and way more complicated. The fact that digoxin barely crosses while methadone zips right through? Mind blown. And those placenta-on-a-chip models? 92% accuracy? That’s like having a crystal ball for pregnancy safety. We’re getting there. 👏

Chima Ifeanyi

February 20, 2026 AT 03:34Per the literature, the transplacental flux of xenobiotics is governed by a tripartite framework: passive diffusion, carrier-mediated transport, and active efflux. The dominance of P-gp/BCRP in the syncytiotrophoblast layer creates a pharmacological bottleneck that is non-linear across gestational windows. Moreover, the ontogeny of these transporters exhibits a sigmoidal trajectory, peaking in late second trimester - a critical oversight in current clinical guidelines.

Also, acetaminophen? It’s not benign. The glutathione depletion pathway in fetal hepatocytes is underappreciated. We’re in a pharmacovigilance crisis.

THANGAVEL PARASAKTHI

February 22, 2026 AT 02:36so i was on valproic acid during my pregnancy and my kid is 5 now and super smart. i think the stats are just scare tactics. maybe some ppl have bad outcomes but not everyone. i dont think we should scare pregnant people with numbers. just talk to ur doc and chill.

Chelsea Deflyss

February 22, 2026 AT 23:51Anyone else notice how this article says ‘we don’t know enough’ but still gives exact percentages like it’s gospel? 65-75% for methadone? Where’s the citation? I’ve seen this same stat repeated 10 times with no source. This isn’t science - it’s guesswork dressed up in lab coats.

Scott Conner

February 23, 2026 AT 12:32Wait - so if P-gp gets blocked by methadone, and that increases chemo exposure… does that mean chemo patients who are also on methadone for pain are at higher risk? Or is it the other way around? I’m confused. Does this mean we need to test drug combos in pregnancy? Like… a whole new field?

Marie Fontaine

February 23, 2026 AT 19:59