When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $6 copay for your generic blood pressure pill, it’s easy to think the system works. But if you’ve ever traveled abroad and bought the same pill for $2-or seen a friend in Canada pay $10 for a brand-name drug that costs $400 here-you know something’s off. The truth about drug prices isn’t simple. The U.S. pays more for brand-name drugs than any other country. But when it comes to generic drugs, the story flips. Americans often pay less for generics than people in Germany, Japan, or France.

Generics Are Cheaper in the U.S.-Here’s Why

Over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. That’s not a coincidence. It’s the result of aggressive competition, fast FDA approvals, and powerful negotiating power from Medicare and large pharmacy benefit managers. When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, multiple companies rush to make the same pill. As soon as two or three generics hit the market, the price drops to about 35% of the original. By the time five or six companies are making it, the price falls to just 15-20%.

That’s why the average generic copay in the U.S. is $6.16, according to the FDA’s 2023 Savings Report. Compare that to the average brand-name copay of $56.12-nearly nine times higher. In fact, 93% of generic prescriptions in the U.S. cost under $20. That’s not true in most other countries. In the UK, France, and Japan, even after government price controls, generic drugs often cost 30-50% more than in the U.S.

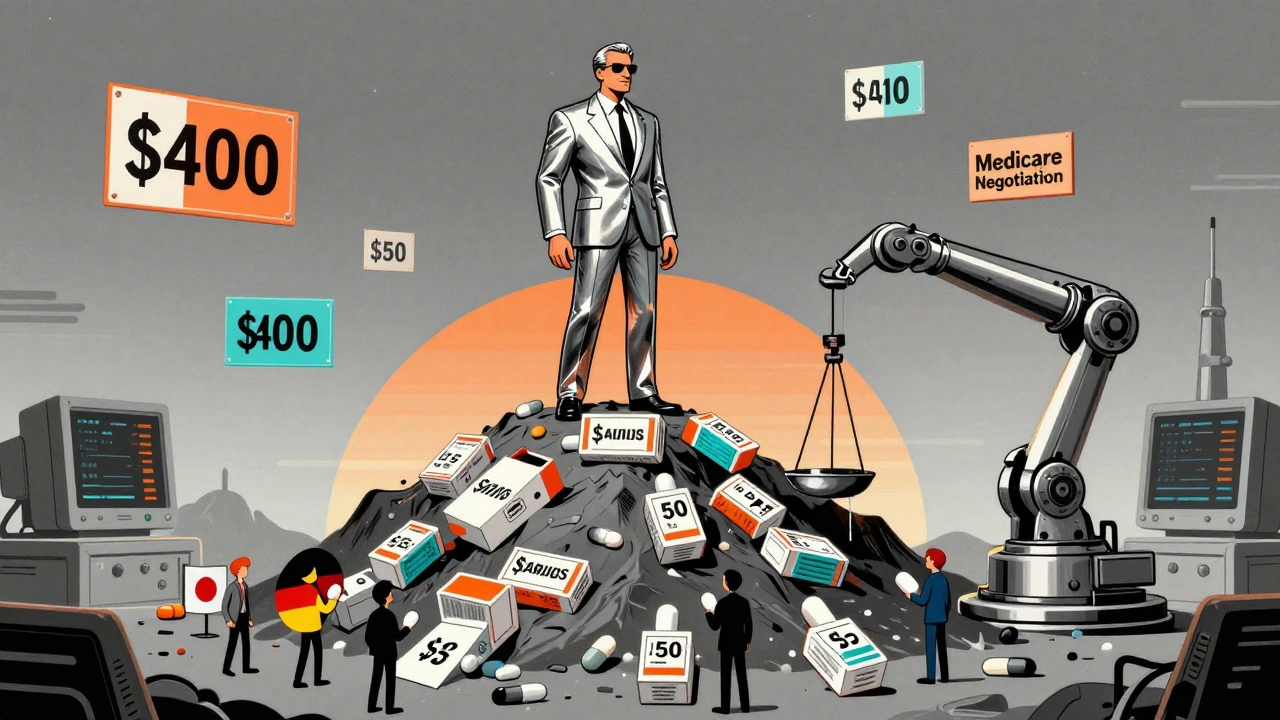

But Brand-Name Drugs? The U.S. Pays the Most

Here’s where things get expensive. The U.S. pays 308% more than other OECD countries for brand-name drugs. For some drugs, the difference is extreme. Take Jardiance, a diabetes medication. Medicare’s negotiated price in 2025 was $204 per month. In Japan, the same drug costs $52. In Australia, it’s $48. That’s more than four times the price here.

Why? Because the U.S. doesn’t have a central agency that negotiates drug prices for everyone. Instead, private insurers, Medicare, and pharmacies negotiate separately. That means drugmakers can set high list prices and still make money through rebates and discounts. The list price you see on a drug’s sticker? That’s not what most people pay. But for uninsured patients or those in high-deductible plans, that list price is what they’re stuck with.

France and Japan keep brand-name prices low by setting strict price caps. Germany and the UK use value-based pricing-they pay what they think the drug is worth, not what the company demands. The U.S. doesn’t do that. As a result, originator drugs (the first version made by the original company) cost 422% more here than elsewhere.

The Net Price Paradox: Why Some Studies Say the U.S. Pays Less

You might read a headline saying, “U.S. drug prices are lower than Europe’s.” That sounds wrong. But it’s not false-it’s incomplete. A 2024 study from the University of Chicago looked at net prices-what the government and insurers actually pay after rebates, discounts, and secret deals. They found that for public programs like Medicare Part D, the U.S. pays 18% less on average than Canada, Germany, and the UK.

How? Because U.S. insurers are better at squeezing rebates. Drugmakers give discounts to get their drugs on insurance formularies. The more patients a drug reaches, the bigger the discount. Since the U.S. has such a huge market, companies offer steep deals to get on Medicare and big insurer lists. That drives down the final price. But that savings doesn’t reach everyone. Uninsured patients? They pay full list price. People on high-deductible plans? They pay full price until they hit their deductible.

How Generic Competition Drives Prices Down

The FDA tracks how many companies make each generic drug. Their data shows a clear pattern: more competitors = lower prices. When only one company makes a generic, it costs about 60% of the brand. Add a second, and it drops to 40%. With three or more, it falls to 15-20%. That’s why some generics-like metformin for diabetes or lisinopril for blood pressure-cost less than $5 for a 30-day supply.

But here’s the catch: sometimes, too much competition kills the market. If prices drop too low, manufacturers stop making the drug because it’s not profitable. That happened with some antibiotics and older heart medications. Then, only one company is left-and they raise the price. That’s why some “generic” drugs suddenly become expensive. It’s not a glitch. It’s a market failure.

What’s Happening Now? Medicare Negotiation and Global Pressure

In 2025, Medicare started negotiating prices for 10 high-cost brand-name drugs. The results? Every single negotiated price was higher than what other countries pay. In 9 out of 10 cases, Japan, Australia, and Germany paid less. The only exception? Stelara, a psoriasis drug. Germany’s price was slightly higher than Medicare’s.

That’s a wake-up call. Even with negotiation, the U.S. still pays more. And now, the government is preparing to negotiate more drugs. The next round will include drugs for Alzheimer’s, cancer, and autoimmune diseases. If those prices still stay above global levels, pressure will grow to change the system.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is being accused of “free riding.” Other countries pay less because they rely on American-funded research. Drug companies spend billions in the U.S. to develop new drugs, then sell them cheaply overseas. Some experts argue that if other countries paid more, innovation would keep going. Others say that’s a myth-most breakthroughs come from public research, not private profit.

What This Means for You

If you take mostly generics, you’re getting a deal. Your $6 pill is cheaper than in most of the world. But if you need a brand-name drug-like insulin, biologics, or cancer treatments-you’re paying more than anyone else. There’s no magic fix. But you can take action:

- Ask your doctor if a generic is available-even for newer drugs, biosimilars are starting to appear.

- Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare prices at local pharmacies. Sometimes, the cash price is lower than your insurance copay.

- If you’re on Medicare, check if your drug is in the negotiation list. If it is, your price may drop next year.

- Don’t assume your insurance is saving you money. Ask for the net price after rebates. You might be surprised.

The system is broken, but not hopeless. The U.S. has the most competitive generic market in the world. That’s a win. But for the 10% of prescriptions that are brand-name, we’re paying a global premium. Until that changes, the gap will stay wide.

Why Other Countries Can Keep Prices Low

It’s not magic. It’s policy. Countries like Japan and France set price caps before a drug even hits the market. They look at how much it costs to make, how effective it is, and what other countries pay. Then they say, “This is what we’ll pay.” If the company doesn’t agree, they don’t sell it there.

In the U.S., no one sets a cap. Companies can charge what they want. And because Americans are willing to pay-through insurance, out-of-pocket, or government programs-they do. It’s not that other countries are smarter. It’s that they’re willing to say no.

The Future of Generic Drug Prices

By 2030, the FDA expects over 1,000 new generic drugs to hit the market. That could save the U.S. over $100 billion in the next five years. But it depends on one thing: keeping competition alive. If big companies buy up small generic makers to limit supply, prices will rise. If regulators keep approving new competitors, prices will keep falling.

The biggest threat isn’t lack of innovation. It’s lack of competition. And that’s something we can fix-with the right policies, and the right pressure on drugmakers.

Are generic drugs in the U.S. really cheaper than in other countries?

Yes, for most common generics like metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin, U.S. prices are 30-50% lower than in countries like Canada, Germany, and the UK. This is because the U.S. has more generic manufacturers competing, faster FDA approvals, and strong negotiation power from large insurers and Medicare. The FDA confirms that with three or more generic makers, prices drop to 15-20% of the brand-name cost.

Why do U.S. brand-name drugs cost so much more?

The U.S. doesn’t regulate drug prices. Drugmakers set high list prices and rely on rebates to private insurers to stay profitable. Other countries negotiate prices upfront or cap them by law. In Japan and France, the government decides what a drug is worth before it’s sold. In the U.S., there’s no such limit. That’s why originator drugs cost 422% more here than elsewhere.

Does Medicare negotiation lower drug prices to global levels?

No. Even after Medicare negotiates prices for the first 10 drugs in 2025, every negotiated price was higher than what other countries pay. For example, Medicare pays $204 for Jardiance, while Japan pays $52. The negotiation program helps reduce costs, but it doesn’t close the gap with global prices. The U.S. still pays more for nearly all brand-name drugs.

Can I buy cheaper drugs from other countries?

Legally, importing prescription drugs from other countries is not allowed by the FDA for personal use, with very few exceptions. But many Americans still do it through online pharmacies. While some offer real savings, others sell counterfeit or expired drugs. The safest way to save is to use U.S.-based discount programs like GoodRx or ask your pharmacist about cash prices-sometimes they’re lower than insurance copays.

Why do some generic drugs suddenly become expensive?

When too many companies make a generic, profits get too thin. Some manufacturers quit the market. If only one or two remain, they can raise prices. This happened with drugs like doxycycline and albuterol. The FDA calls this a “market failure.” It’s rare, but it’s real. More competition usually means lower prices-but only if enough companies stay in the game.

What’s the difference between list price and net price?

List price is the sticker price drugmakers charge pharmacies. Net price is what insurers and government programs actually pay after rebates and discounts. In the U.S., the net price for public programs is often lower than in other countries because of aggressive rebate deals. But uninsured patients pay the full list price-which is why drug costs feel so high for them.

Saket Modi

December 2, 2025 AT 17:50Girish Padia

December 4, 2025 AT 08:27Chris Wallace

December 5, 2025 AT 12:04william tao

December 7, 2025 AT 00:33John Webber

December 8, 2025 AT 11:21Sheryl Lynn

December 8, 2025 AT 14:59Paul Santos

December 10, 2025 AT 12:23Fern Marder

December 11, 2025 AT 22:57Carolyn Woodard

December 13, 2025 AT 02:30Genesis Rubi

December 14, 2025 AT 05:42Doug Hawk

December 14, 2025 AT 08:57