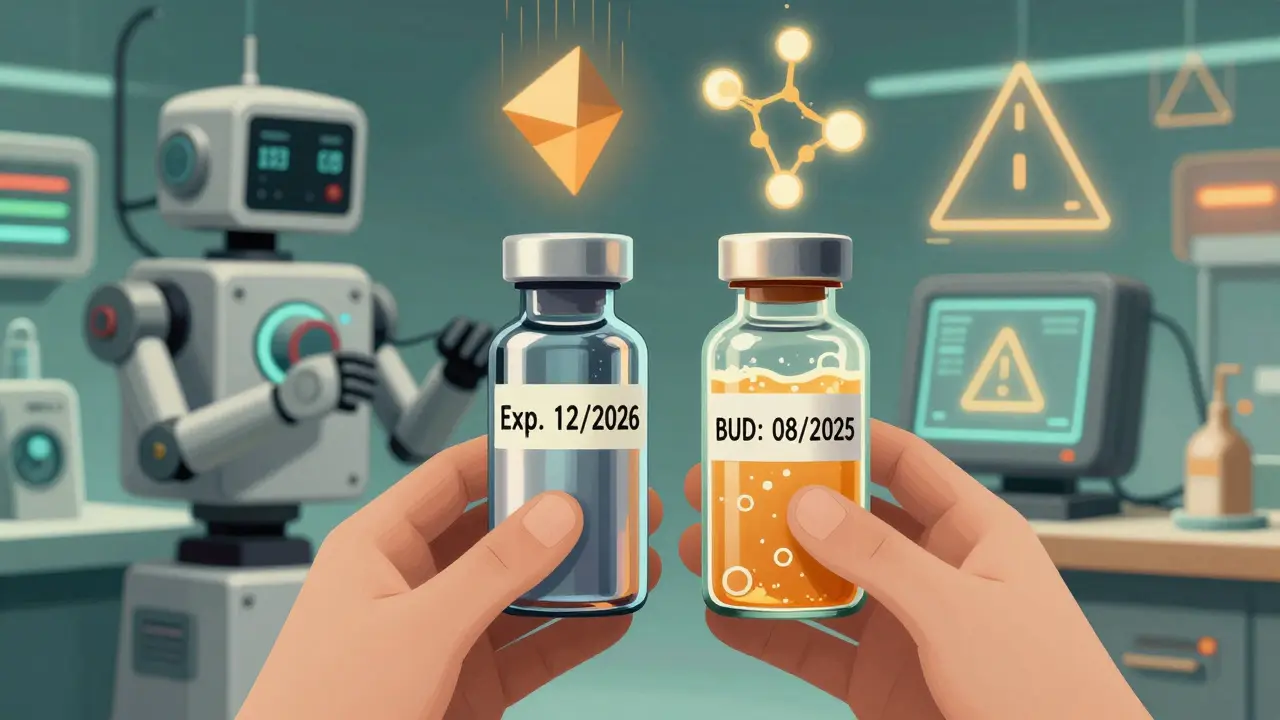

When you pick up a prescription, you might notice two different dates on the label: one printed by the manufacturer, and another written by the pharmacy. One says expiration date. The other says beyond-use date. They look similar, but they’re not the same. And confusing them could mean taking a drug that doesn’t work-or worse, one that’s unsafe.

Let’s cut through the noise. This isn’t about legal jargon or pharmacy rules. It’s about knowing when your medicine is still good, and when it’s time to toss it. Whether you’re managing a chronic condition, caring for a child, or just trying to avoid wasting money, understanding the difference between these two dates matters.

What Is a Manufacturer Expiration Date?

An expiration date is stamped on every FDA-approved medication you buy off the shelf. It’s not arbitrary. It’s the result of years of testing. Manufacturers put drugs through extreme conditions-heat, humidity, light, time-to see how long they hold up. The FDA requires this testing before a drug can be sold.

For example, a bottle of amoxicillin might say "Exp. 12/2026". That means the manufacturer guarantees it will still have at least 90% of its labeled strength until that date, as long as it’s stored the way the label says: dry, cool, and in its original container. Even if you open it, the expiration date still stands. The testing accounts for normal handling.

These dates usually range from 1 to 5 years after manufacturing. Some last longer-studies have shown that many drugs remain stable for over a decade if stored perfectly. But the FDA doesn’t allow that to be printed on the label. Why? Because real-world storage is unpredictable. Your medicine might sit in a hot car, a steamy bathroom, or a sunlit drawer. That’s why the expiration date includes a safety buffer.

Bottom line: If it’s a factory-made pill, liquid, or injection with a manufacturer’s label, the expiration date is your final deadline. Don’t use it after.

What Is a Beyond-Use Date?

A beyond-use date (BUD) appears on medications that have been changed after leaving the factory. This includes compounded drugs-custom-made mixes created by pharmacists for people who can’t take standard versions. Maybe you’re allergic to dye in the commercial pill. Maybe your child needs a liquid form of a drug that only comes as a tablet. Or maybe your doctor needs a specific dose that doesn’t exist on the market.

When a pharmacy prepares one of these custom medications, they can’t rely on the manufacturer’s expiration date. Why? Because the drug has been altered. The chemical balance, the preservatives, the packaging-all of it changes. That’s why a pharmacist assigns a BUD.

Unlike expiration dates, BUDs are not set by long-term lab tests. They’re based on guidelines from the United States Pharmacopeia (USP). These rules consider how the drug was made, what it’s made of, and how it’s stored. For example:

- A simple pill mixed with a liquid might get a BUD of 14 days if refrigerated.

- A cream compounded with multiple ingredients might last up to 6 months if kept cool and dark.

- A sterile IV solution? That could be 45 days if stored properly.

Here’s the catch: BUDs are almost always shorter than expiration dates. That’s not because compounding is risky-it’s because the rules are conservative. Pharmacists are told to assume the worst-case scenario: poor storage, contamination, unstable ingredients. It’s better to throw away a little too soon than risk a patient getting sick.

Key Differences Between Expiration Dates and Beyond-Use Dates

Here’s what you need to remember when you see either date:

| Feature | Manufacturer Expiration Date | Pharmacy Beyond-Use Date (BUD) |

|---|---|---|

| Applies to | Factory-made, FDA-approved drugs | Compounded, repackaged, or altered medications |

| Determined by | Manufacturer stability testing (FDA-regulated) | Pharmacist using USP guidelines |

| Typical time range | 12-60 months from manufacturing | 14 days to 1 year (often under 6 months) |

| Storage conditions | Based on original packaging and labeling | May require refrigeration even if original didn’t |

| Potency guarantee | 90%+ potency until date | No formal guarantee-based on risk assessment |

| Legal basis | Federal (FDA 21 CFR 211.137) | State pharmacy boards + USP Chapters <795>/<797> |

Notice how the BUD isn’t about how long the drug lasts-it’s about how long the pharmacy can reasonably say it’s safe after being touched. That’s why a drug with a 2027 expiration date might get a 2025 BUD if it’s repackaged into a blister pack. The pharmacy doesn’t know how you’ll store it. So they shorten the clock.

Why This Matters for Patients

Let’s say you’re on a compounded thyroid medication. The bottle says "BUD: 08/2025". But the original vial of powder the pharmacist used had an expiration date of "Exp. 11/2026". You might think, "It’s still good for over a year. Why is it only good until August?"

That’s a common misunderstanding. The powder was stable. But once it was mixed with a liquid, exposed to air, and put into a new container, it became a new product. No more manufacturer guarantee. Only the pharmacist’s best guess based on safety rules.

A 2022 survey found that 68% of patients on compounded meds ended up throwing away unused medicine because the BUD ran out before they finished their course. That’s not just waste-it’s cost. Compounded drugs can cost 2 to 5 times more than regular ones. Losing even a few doses adds up.

And storage matters more than you think. A commercial antibiotic might say "Store at room temperature". But if that same drug is compounded into a liquid, the BUD might require refrigeration. Why? Because the preservatives used in commercial products are often left out in custom mixes. That makes them more prone to bacteria growth.

One patient in Sydney told their pharmacist: "I left my compounded cream on the bathroom counter for two weeks. Is it still okay?" The answer? No. Even if it looks fine. Even if it smells fine. The risk isn’t worth it.

What Should You Do?

Here’s your simple action plan:

- Check both dates when you get your medicine. Look for the manufacturer’s label on the original bottle or box. Then look for the pharmacy’s sticker with the BUD.

- Follow the earlier date. If the BUD is before the expiration date, the BUD wins. Always.

- Store it right. If the pharmacy says "Refrigerate", don’t leave it on the counter. If they say "Keep away from light", put it in a drawer.

- Don’t guess. If you’re unsure, call the pharmacy. They’ll tell you whether it’s still safe.

- Dispose properly. Never throw expired or out-of-date meds in the trash. Most pharmacies offer free take-back programs. Use them.

There’s no such thing as a "grace period" with medications. Even if it looks fine, even if it smells fine, even if it’s only a few days past the date-don’t risk it. Potency drops. Chemicals break down. Bacteria grow. And you won’t know until it’s too late.

What’s Changing in 2026?

The rules around BUDs are tightening. In 2023, the USP proposed updates to Chapters <795> and <797> that will reduce maximum BUDs for high-risk compounds by up to 30%. Why? Because too many pharmacies were stretching timelines too far. The FDA issued 27 warning letters to compounding pharmacies in 2022 alone for improper dating.

As personalized medicine grows, so does the need for clear, consistent rules. The compounding pharmacy market in the U.S. is now worth over $11 billion. More patients rely on these custom drugs. That means more pressure to get dating right.

For now, the message is simple: expiration dates are for factory-made drugs. Beyond-use dates are for everything else. And when in doubt, always trust the pharmacy’s label.

Can I use a drug after its expiration date if it looks fine?

No. Even if the pill hasn’t changed color or smell, its potency may have dropped below safe levels. The FDA doesn’t recommend using any medication past its expiration date because storage conditions vary too much in real life. Heat, moisture, and light degrade drugs in ways you can’t see.

Why does my compounded medication have a shorter date than the original bottle?

Because once a drug is altered-mixed, diluted, repackaged-it’s no longer the same product the manufacturer tested. The original expiration date only applies to the unopened, factory-sealed version. After that, the pharmacy assigns a beyond-use date based on how stable the new mixture is, and how it’s stored. It’s not about the ingredients-it’s about what happened after they left the factory.

Is it safe to use a drug past its beyond-use date if I haven’t opened it?

No. The beyond-use date is based on the date the pharmacy prepared or repackaged the medication, not when you opened it. Even if the container is sealed, the formulation may have degraded since it was made. The BUD is not a "best by" date-it’s a safety cutoff.

Can I ask my pharmacist to extend the beyond-use date?

No. Beyond-use dates are set according to strict USP guidelines and state pharmacy laws. Pharmacists can’t legally extend them, even if you’re paying for the medication. If you need more, you’ll need a new prescription. This protects you from using unstable or contaminated drugs.

What happens if I accidentally take a drug past its date?

In most cases, you won’t get seriously sick-but the drug likely won’t work as well. For antibiotics, this could mean an infection doesn’t clear. For heart or seizure meds, it could mean dangerous fluctuations in your condition. If you’ve taken something past its date, contact your doctor. Don’t wait for symptoms.

Next Steps

If you’re on a compounded medication, make sure you understand its BUD. Ask your pharmacist to explain how it was made and how to store it. Keep a note on your phone with the date and storage instructions.

If you’re managing medications for someone else-like an elderly parent or a child-check the dates every time you refill. Don’t assume the pharmacy did it right. Double-check the label against the original packaging.

And if you’re ever unsure? Call the pharmacy. They’re there to help. Better to ask once than risk your health.

Lyle Whyatt

February 8, 2026 AT 06:32Man, I wish I'd known this before I threw out my compounded thyroid med last year because the BUD ran out. I was so mad-paid $300 for a 30-day supply, only used half, and had to toss the rest. Turns out, I wasn't alone. 68% of people do this? That’s insane. My pharmacist didn’t even explain the difference between expiration and BUD when I picked it up. Just handed me the bottle like it was a bag of chips. If you’re on a custom med, ask for a printed one-pager. Seriously. Save yourself the cash and the panic.

Also, I left my cream on the counter for two weeks after my cat knocked it over. Thought, ‘Eh, it’s still sealed.’ Nope. Not worth the risk. Now I keep mine in a locked Tupperware in the fridge with a sticky note that says ‘DO NOT TOUCH.’

Sam Dickison

February 9, 2026 AT 20:20From a pharmacy tech’s POV: BUDs aren’t arbitrary. We follow USP 795/797 like gospel. If you’re compounding a non-sterile oral liquid with no preservatives, 14 days refrigerated is the max-no wiggle room. We’ve seen patients try to stretch it, and yeah, sometimes it looks fine. But bacteria? Mold? You won’t see it until you’re sick. One case in Houston: patient developed sepsis from a compounded topical that ‘looked okay.’ We don’t cut corners because we’re mean-we cut them because someone died last year doing exactly that.

Brett Pouser

February 10, 2026 AT 21:48Just wanted to say thanks for this breakdown. My mom’s on a compounded hormone cream, and I always thought the pharmacy was just being extra. Now I get it-she’s not getting a ‘discount’ version of the drug. She’s getting something totally new. The original vial’s expiration? Irrelevant. It’s like asking if last year’s cake batter is still good after you’ve mixed in new eggs and flour. It’s a different recipe now. And we treat it like it’s fragile because it is.

Also, fridge storage? Non-negotiable. We’ve got a little labeled bin in our fridge just for meds. No leftovers. No debates.

Simon Critchley

February 12, 2026 AT 10:57OMG. I’ve been using my compounded antifungal for 8 months. It’s still in the original tube. It’s still white. It smells minty. I’ve been fine. Why does the BUD say 60 days?! This is a scam. USP guidelines? More like ‘overcautious bureaucracy.’ I’ve got a degree in chemistry-I know what stability looks like. And this? This is fearmongering dressed up as science. They’re not protecting us-they’re protecting their liability. I’m not throwing it out. I’m keeping it. And if I get sick? At least I’ll know who to blame.

PS: I’ve also been using expired amoxicillin for 4 years. Still works. #PharmaLies

John McDonald

February 14, 2026 AT 02:08Let me just say this: I used to be the guy who hoarded expired meds. ‘It’s just a few days past!’ I’d say. Then my dad had a seizure because his anti-epileptic lost potency. He didn’t die-but he spent 3 weeks in the hospital. Since then? I check every bottle. I label them with masking tape. I take photos of the BUD on my phone. I set reminders. I’m not a doctor. I’m not a pharmacist. But I’m the guy who makes sure the meds don’t kill my family. If this post saves one person from a hospital trip? Worth it.

Also, don’t trust your memory. Write it down. Or better yet-ask your pharmacist to text you the date. They’ll do it.

Joseph Charles Colin

February 15, 2026 AT 14:36For those asking about extending BUDs: it’s not a matter of ‘trust.’ USP 795 requires stability data for every compounded formulation, and that data is derived from real-world degradation studies-not guesswork. A BUD of 14 days for a non-preserved oral liquid? That’s based on microbiological challenge testing. Even if the container is sealed, the preservative system is absent. Bacteria can grow in water-based solutions faster than you think. Pseudomonas. Aspergillus. These aren’t theoretical. They’re documented. The FDA doesn’t issue warning letters for fun. They do it because people get sick. And yes-sometimes they die. You’re not a scientist. Your pharmacist is. Trust the process.

John Sonnenberg

February 17, 2026 AT 06:54So… let me get this straight. You’re telling me that if I take a perfectly good, factory-made pill, and the pharmacy puts it in a different container, suddenly it’s ‘unstable’? And I have to throw it out in 60 days? What? That’s like saying if I pour your soda into a different cup, it becomes poison. This is ridiculous. Who decided this? A committee of people who’ve never held a pill? I’m not a lab rat. I’m a human being. I know when something’s good. And if it looks, smells, and tastes fine? It’s fine. The system is broken. And I’m not playing along anymore.

Joshua Smith

February 18, 2026 AT 15:40Thanks for this. I’ve been on a compounded asthma inhaler for years and never understood why the date was so short. My pharmacist actually sat down with me and walked through the USP guidelines. It was eye-opening. Turns out, the base solution they use has no preservatives because of my allergies, so it’s basically a sterile water + drug mix. That’s why refrigeration matters so much. I didn’t realize how much work goes into making these. I used to think they were just ‘custom pills.’ Now I see it’s more like custom chemistry. And I’m grateful. If you’re on one, ask your pharmacist to explain it. They’ll love you for asking.

Jessica Klaar

February 20, 2026 AT 11:41I’m a nurse and I’ve seen too many elderly patients take expired meds because ‘they’ve always taken it.’ One woman took a 7-year-old blood pressure pill and ended up in the ER with a stroke. The pill was still in its original bottle. The expiration date was clearly printed. She said, ‘It didn’t taste weird.’ That’s not how this works. I keep a printed chart in my mom’s medication box with the dates and storage instructions. I even color-code: red for BUD, green for expiration. It’s not fancy-but it saves lives. Don’t rely on memory. Write it down. And if you’re unsure? Call the pharmacy. They’re paid to answer that question.

PAUL MCQUEEN

February 21, 2026 AT 16:27Wow. Another ‘pharma tells you what to do’ post. Next they’ll say we can’t breathe air because ‘it’s not FDA-approved.’ Why do we let corporations dictate our health? The FDA’s expiration dates are based on profit, not science. They want you to buy new pills every year. The real science? Drugs last decades. Look up the Pentagon’s study on expired antibiotics. They were 90% effective after 15 years. So why do we believe this BUD nonsense? Because we’ve been trained to. Wake up.

glenn mendoza

February 23, 2026 AT 10:47Thank you for this comprehensive and compassionate overview. As someone who has worked in both clinical pharmacy and public health outreach, I can attest that the clarity provided here is not only accurate but desperately needed. The distinction between manufacturer expiration dates and beyond-use dates is a critical patient safety issue that is too often overlooked. Pharmacists are not being overly cautious-we are being ethically responsible. The integrity of a compounded formulation is not a matter of aesthetics or convenience-it is a matter of microbial stability, chemical integrity, and, ultimately, human life. I encourage all patients to engage with their pharmacists-not as customers, but as partners in care. Your health deserves nothing less than rigorous, evidence-based guidance.

Kathryn Lenn

February 24, 2026 AT 17:08