Most people think obesity is just about eating too much and moving too little. But that’s not the full story. Behind the scale, there’s a complex biological system that’s gone off track. Your brain, your hormones, your fat cells-they’re all talking to each other, and in obesity, they’re sending the wrong signals. This isn’t laziness. It’s biology. And understanding how it breaks down is the first step toward fixing it.

The Brain’s Hunger Control Center

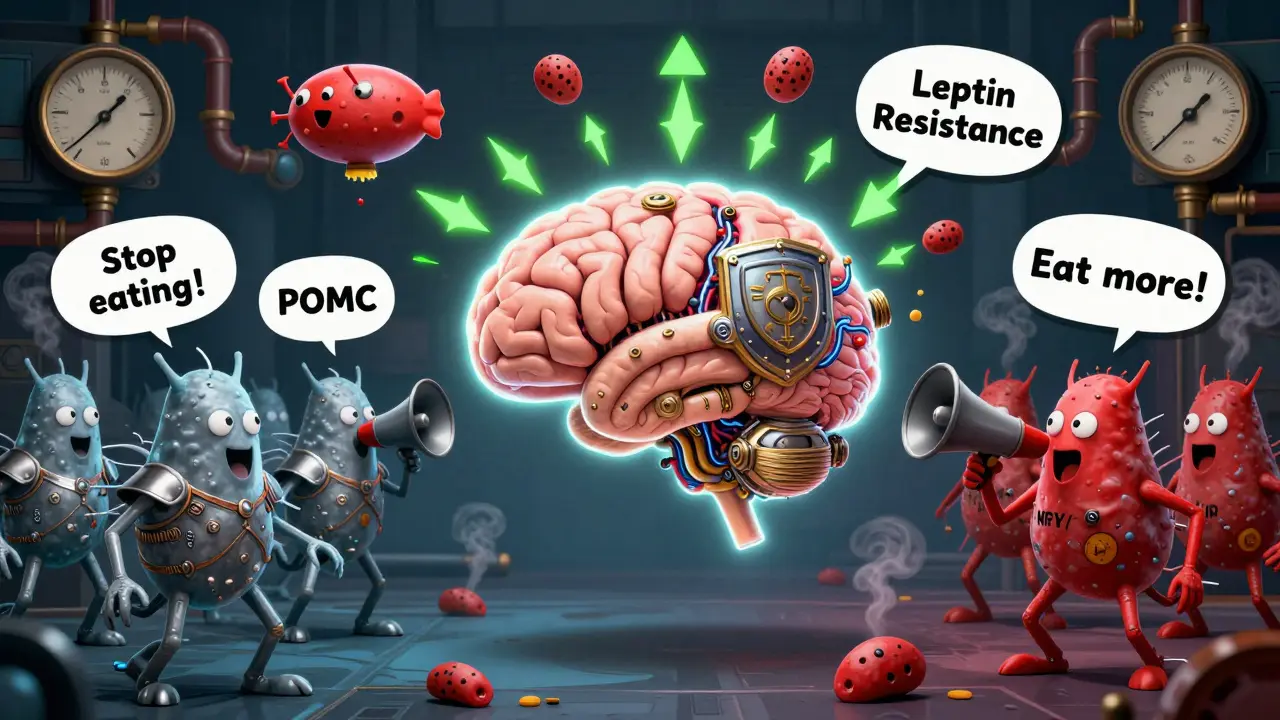

At the heart of it all is a tiny region in your brain called the arcuate nucleus. It’s like the command center for hunger and fullness. Two groups of neurons fight for control: one tells you to stop eating, the other tells you to eat more. The first group, POMC neurons, release a chemical called alpha-MSH. This signal tells your brain you’re full. When it works right, it cuts your food intake by 25% to 40%. The second group, NPY and AgRP neurons, do the opposite. They scream for food. In experiments, turning these neurons on in mice made them eat 300% to 500% more in minutes. That’s not hunger. That’s a biological emergency. These neurons don’t work alone. They listen to your body. Fat cells release leptin, a hormone that tells your brain how much fat you have. In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, they jump to 30-60 ng/mL. You’d think more leptin would mean less hunger. But here’s the twist: your brain stops listening. This is called leptin resistance. It’s not that you don’t have enough leptin. You have way too much, and your brain ignores it. That’s why dieting feels so hard-your body thinks it’s starving, even when you’re overweight.The Hormones That Trick Your Brain

Leptin isn’t the only player. Insulin, which rises after meals, also tells your brain to cut back on eating. In a fasted state, insulin hovers around 5-15 μU/mL. After you eat, it spikes to 50-100 μU/mL. In obesity, insulin levels stay high all the time, and your brain starts ignoring it too. This is insulin resistance in the brain, and it’s just as damaging as insulin resistance in your muscles or liver. Then there’s ghrelin-the only hormone that makes you hungry. It climbs before meals, from 100-200 pg/mL when you’re fasting to 800-1000 pg/mL right before you eat. In obese people, ghrelin doesn’t drop as it should after eating. That means you feel hungry again sooner. It’s like your hunger button is stuck. Another key player is pancreatic polypeptide (PP). It’s released after meals and slows digestion while reducing appetite. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are abnormally low-15-25 pg/mL instead of the normal 50-100 pg/mL. Your body isn’t signaling fullness properly. You keep eating because your brain doesn’t get the message.

Why Diets Fail: The Metabolic Slowdown

Losing weight isn’t just about willpower. Your body fights back. When you drop weight, your metabolism slows down. That’s not a myth. It’s science. Your body thinks it’s in famine mode. It burns fewer calories, even at rest. Studies show that after weight loss, energy expenditure drops by 15-20% more than expected based on your new size. That’s why people regain weight-they’re not eating more, they’re just burning less. This isn’t just about calories in versus calories out. It’s about how your body adjusts its thermostat. The PI3K/AKT pathway, which links leptin and insulin signals, gets disrupted in obesity. When this pathway is blocked, leptin can’t suppress appetite anymore. That’s why drugs that target this pathway, like setmelanotide, work so well in rare genetic forms of obesity-they bypass the broken signal and directly activate the brain’s fullness circuit. Even more surprising: your brown fat, the kind that burns calories to make heat, gets quieter in obesity. Normally, it helps you stay lean. But in overweight people, it’s less active. One study showed that blocking a protein called PTEN in mice turned on brown fat, dropped body weight by 15-20%, and increased appetite. That’s right-burning more calories didn’t make them eat less. It made them hungrier. Your body is trying to balance energy use with energy intake, even when that balance is broken.Sex, Age, and Hormones

Obesity doesn’t affect everyone the same. Women, especially after menopause, are at higher risk. Estrogen helps regulate appetite and energy use. When estrogen drops, so does the brain’s ability to control food intake. Studies in mice without estrogen receptors showed a 25% increase in eating and a 30% drop in energy burning. In humans, women gain 12-15% more belly fat in the five years after menopause-not because they’re eating more, but because their metabolism shifts. Older adults face similar challenges. The mTOR system, which helps regulate energy balance, becomes less responsive with age. This contributes to weight gain even if diet and activity don’t change. And then there’s orexin-a hormone that keeps you alert and awake. In obese people, orexin levels drop by 40%. That might explain why many with obesity feel sluggish. But paradoxically, people with night-eating syndrome have high orexin at night, making them eat when they should be sleeping. It’s messy, unpredictable, and deeply biological.

Sue Stone

January 23, 2026 AT 17:14So it's not just 'eat less, move more'? Wow. This makes so much more sense now.

Oladeji Omobolaji

January 25, 2026 AT 06:06in nigeria we got different probs, but the brain-hormone thing? yeah that tracks. my auntie lost weight after menopause and still ate like a horse. no one believed her.

Janet King

January 27, 2026 AT 01:18Leptin resistance is well-documented in clinical literature. The key is recognizing it as a neuroendocrine disorder, not a behavioral one. This post accurately reflects current endocrinology guidelines.

Vanessa Barber

January 28, 2026 AT 10:19Actually, the ‘metabolic slowdown’ is exaggerated. Studies show most people regain weight because they go back to old habits. Biology doesn’t override willpower-it just makes it harder.

Stacy Thomes

January 30, 2026 AT 07:11THIS. I’ve been fighting this for 12 years. I’m not lazy. I’m not weak. My body is literally screaming at me to eat even when I’m full. Thank you for saying this out loud.

dana torgersen

January 31, 2026 AT 23:36...and yet... the brain’s emergency brake... it’s like... a biological off-switch... but... why... why does it only work in mice? and... why... is... no one... talking... about... the... dopamine... feedback... loop...?

Laura Rice

February 2, 2026 AT 16:54my grandma had type 2 diabetes and obesity and she swore she ate like a bird. she didn't. but she also didn't understand why her body didn't care. this post? it explains why she wasn't lying. it's not her fault. it's her biology. thank you.

charley lopez

February 3, 2026 AT 04:58The PI3K/AKT pathway disruption in hypothalamic neurons is a consistent finding in murine models of diet-induced obesity. However, translational efficacy in humans remains limited due to pleiotropic effects of downstream signaling. Setmelanotide’s success in POMC/LEPR mutations supports receptor-specific targeting but lacks generalizability.

Kerry Moore

February 5, 2026 AT 03:04Thank you for this. I’ve spent years being told I just need to ‘try harder.’ I’ve tried. I’ve starved. I’ve exercised until I passed out. And still, the hunger doesn’t stop. This isn’t weakness. It’s a malfunctioning system. We need more doctors who understand this, not just more willpower.

Anna Pryde-Smith

February 6, 2026 AT 06:56OH MY GOD. I’ve been screaming this for years. People call me lazy because I can’t lose weight. I’m not lazy-I’m biologically hijacked. And now you’ve got science backing me up? I’m crying. I’m so tired of being blamed.

Sallie Jane Barnes

February 7, 2026 AT 17:29Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse, and I see patients every day who are shamed for their weight. This isn’t about willpower-it’s about neurochemistry, hormones, and evolution. We need to change the narrative. And we need better treatments, not judgment.

Kerry Evans

February 9, 2026 AT 13:19Interesting. But you’re ignoring the role of processed foods. The real problem is industrial food engineering designed to override satiety signals. No amount of biology explains why people eat 5000 calories a day of chips and soda. It’s not the brain-it’s the food industry.