When a doctor prescribes a pill that contains two or more drugs in one tablet-like a combination of blood pressure meds or HIV antivirals-it’s not the same as prescribing a single drug. But when that prescription hits the pharmacy counter, pharmacists are often caught between state laws written for single-drug generics and the reality of modern combination therapies. This mismatch creates real risks for patients and confusion for pharmacists. The system wasn’t built for this.

What Exactly Is a Combination Drug?

A combination drug, or fixed-dose combination (FDC), is a single dosage form that contains two or more active pharmaceutical ingredients. Think of ATRIPLA, which combines efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir into one pill for HIV treatment. Or a blood pressure pill that mixes an ACE inhibitor with a diuretic. These aren’t just convenience products-they’re designed to improve adherence, reduce pill burden, and sometimes even enhance effectiveness.

They’re not new. Fixed-dose combinations have been used for decades in TB and HIV treatment. But today, they’re exploding in use. From diabetes and heart disease to cancer and mental health, combination products now make up a growing share of new drug approvals. In fact, the FDA approved 37 combination drug products between 2015 and 2022, while approving over 1,200 single-entity drugs in the same period. That gap shows how much the market has shifted-and how slow the rules have been to catch up.

Why Substitution Laws Don’t Work for Combination Drugs

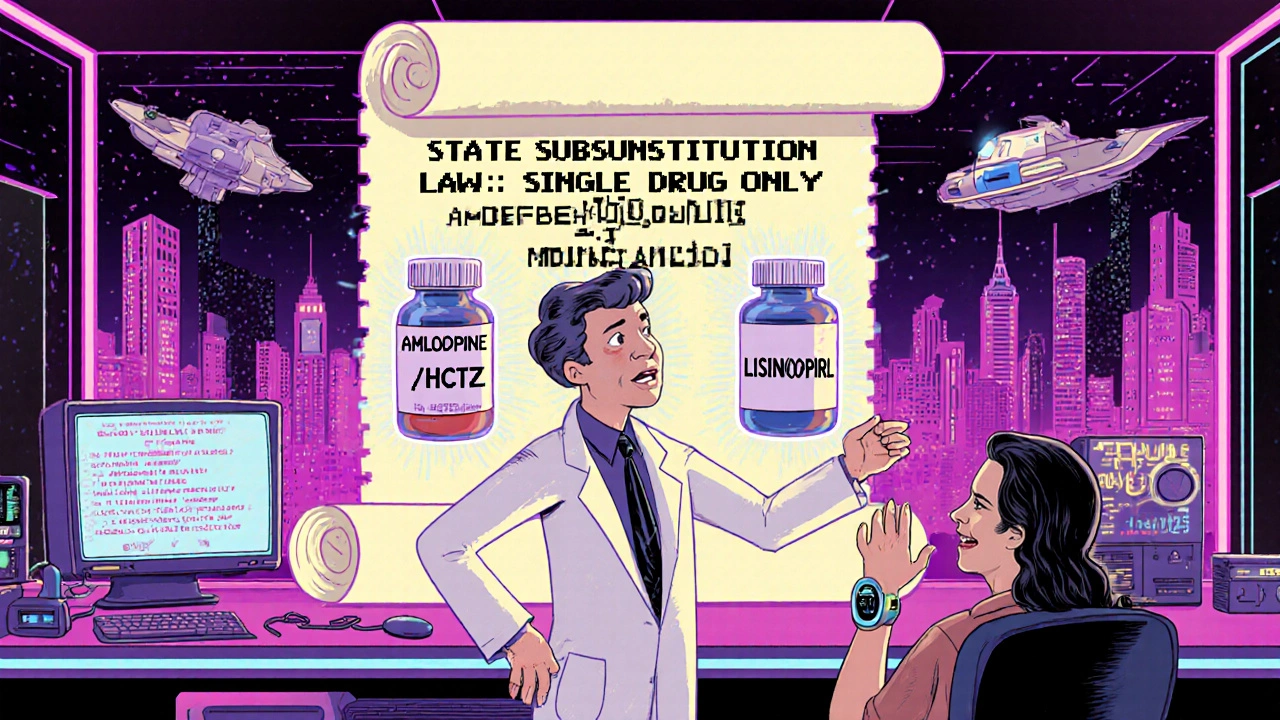

Most U.S. states have generic substitution laws that let pharmacists swap a brand-name drug for a cheaper generic version-as long as it contains the same active ingredient. That works fine for a single-drug pill like lisinopril. But what happens when the prescription is for a combination drug like Amlopidine/Hydrochlorothiazide? Can the pharmacist swap it for a different combo that includes the same two drugs? What if the patient’s original prescription was for just one of those drugs, and the pharmacist wants to switch them to a combo pill to simplify things?

Here’s the problem: traditional substitution laws assume one active ingredient equals one substitution. But combination drugs have multiple ingredients. The FDA defines a combination product as having two or more regulated components-drugs, biologics, or devices-packaged together. That means even if two pills have the same two drugs, differences in release timing, ratios, or inactive ingredients can make them non-interchangeable.

Take the case of a patient on a specific combination of pembrolizumab and lenvatinib for kidney cancer. Even if another combo contains the same two drugs, if the dosing schedule or delivery mechanism is different, swapping them could be dangerous. Yet many state laws don’t distinguish between simple and complex combinations. Pharmacists are left guessing.

The Legal Gray Zone: Who Can Substitute What?

Pharmacists aren’t doctors. In most states, they can’t change a prescription without prescriber approval. But many states allow them to substitute generics-if the drugs are therapeutically equivalent. The issue? Therapeutic equivalence for combination products isn’t clearly defined.

The Therapeutic Substitution Consensus Group, made up of European experts, draws a clear line: generic substitution means swapping one formulation of the same drug for another. Therapeutic substitution means swapping one drug for a different one with a similar effect-like switching a beta-blocker for an ACE inhibitor. But when you’re dealing with a combo pill that has two or more drugs, neither category fits.

Alberta’s College of Pharmacy spells it out: if a patient is prescribed a single drug, and the pharmacist wants to switch them to a combo pill containing that drug plus another, that’s considered starting new therapy. That requires a new prescription. You can’t legally do it at the counter, even if it makes sense clinically.

And it gets messier. Some states allow pharmacists to substitute a combo for another combo with identical ingredients. Others don’t. In Texas, the rules are vague. In California, pharmacists can substitute only if the product is on the FDA’s Purple Book as therapeutically equivalent. But the Purple Book doesn’t even list most combination products yet.

That’s why a 2022 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found 68% of independent pharmacists ran into substitution dilemmas at least once a month. Over 40% said they refused to substitute because they weren’t sure if it was legal.

Real-World Risks: When Substitution Goes Wrong

It’s not just about legality-it’s about safety. Combination drugs often treat chronic conditions where precise dosing matters: heart failure, epilepsy, HIV, bipolar disorder. Many have a narrow therapeutic index-meaning the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is tiny.

The American Heart Association warned in 2023 that inappropriate substitution of cardiovascular combination therapies could lead to adverse events in up to 8% of patients, especially older adults with multiple conditions. One wrong swap-like replacing a combo with a different ratio of drugs-could cause electrolyte imbalances, kidney stress, or uncontrolled blood pressure.

And it’s not just physical risks. When patients are switched without their knowledge, they may not realize their meds have changed. They might stop taking them if they think the new pill looks different. Or they might experience side effects they didn’t have before and assume it’s their condition worsening.

There’s also the legal risk for pharmacies. In the 2022 case Smith v. CVS Caremark, a patient was switched from a prescribed combination drug to a different one that included an extra active ingredient. The court ruled that pharmacists can’t add drugs not listed on the original prescription-even if the change seems beneficial. That decision set a precedent: substitution without explicit prescriber approval is illegal.

Cost Savings vs. Patient Safety: The Economic Pressure

Let’s be honest: the push for substitution isn’t about confusion. It’s about money.

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. but only 23% of total drug spending. Combination products? They’re expensive. A single branded combo pill can cost hundreds of dollars a month. If pharmacists could swap them for cheaper alternatives, insurers and Medicare would save billions.

Dr. Jane Chen from ICER estimates that expanding substitution for combination products could cut medication costs by 15-25% for chronic conditions. The NHS in England saved £280 million annually since 2019 by implementing strict therapeutic substitution protocols for cardiovascular combos.

But here’s the catch: those savings come with trade-offs. The European Medicines Agency explicitly warns against therapeutic substitution of complex combination products without physician oversight. The FDA’s 2022 draft guidance acknowledges the tension, calling for clearer standards before allowing substitution.

And the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 is pushing Medicare Part D to encourage substitution where appropriate. That means pressure is rising-not just from insurers, but from federal policy.

What’s Changing? New Rules on the Horizon

Change is coming, but slowly.

In 2023, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy proposed model legislation to create a tiered system for substitution:

- Simple combinations: Two well-established drugs (like amlodipine + hydrochlorothiazide). These could be eligible for pharmacist substitution under clear criteria.

- Complex combinations: Novel mechanisms, narrow therapeutic index, or drugs with complex release profiles (like cancer combos or psychiatric FDCs). These would require prescriber approval.

The European Commission has made harmonizing substitution rules for combination medicines a top priority in its 2023 Pharmaceutical Strategy. The FDA is working on updated guidance for demonstrating therapeutic equivalence for FDCs.

But until these rules are adopted and standardized across states, pharmacists are flying blind. And patients are the ones paying the price.

What Patients and Pharmacists Need to Do Now

If you’re a patient on a combination drug:

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the exact same combo as my prescription?”

- Check the pill’s appearance, dosage, and manufacturer. If it’s different, ask why.

- Never assume a substitution is safe just because it’s cheaper.

- Request that your prescriber write “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute” on the prescription if you’re concerned.

If you’re a pharmacist:

- Know your state’s laws. Don’t rely on general guidelines-check your board’s official rules.

- When in doubt, call the prescriber. Better to delay a refill than risk harm.

- Document every substitution decision. If you’re questioned later, you’ll need proof you acted responsibly.

- Push for education. Many pharmacists still don’t understand the difference between generic and therapeutic substitution for combos.

The bottom line? Combination drugs are here to stay. But the rules governing them are stuck in the past. Until we update those rules with clear, science-based standards, substitution will remain a legal minefield-and patients will pay the cost.

Can a pharmacist substitute a combination drug for a single drug?

No. If a prescription is for a single drug, a pharmacist cannot substitute it with a combination product that includes additional active ingredients. That would be considered initiating new therapy, which requires a new prescription from the prescriber. This is clearly stated by pharmacy boards in states like Alberta and Texas.

Are all combination drugs eligible for generic substitution?

No. Only combination products that have been formally rated as therapeutically equivalent by the FDA-listed in the Purple Book-are eligible for substitution. Most combination drugs, especially newer or complex ones, don’t have this designation. Many states don’t allow substitution unless the product is on that list.

Why can’t pharmacists just swap combo pills like they do with single drugs?

Because combination pills contain multiple active ingredients. Even if two combos have the same drugs, differences in ratios, release timing, or inactive ingredients can change how the body absorbs them. A 10mg/5mg combo isn’t the same as a 5mg/10mg combo. Substitution laws were written for single-drug generics and don’t account for this complexity.

Is therapeutic substitution legal for combination drugs?

In most cases, no-not without prescriber approval. Therapeutic substitution means replacing one drug with another that has a similar effect. For combination products, this often means swapping one multi-drug pill for another with different ingredients. That’s considered a change in treatment plan and requires a new prescription. The EMA and FDA both caution against it without clinical oversight.

What should I do if my pharmacist substitutes my combination drug without asking?

Stop taking the new medication immediately. Contact your prescriber to confirm if the change was intentional. Then, file a complaint with your state’s pharmacy board. If the substitution added an ingredient not on your original prescription, it may be illegal. Document the pill’s appearance, name, and dosage for your records.

Ryan Anderson

November 11, 2025 AT 22:20Just had this happen last week with my dad’s blood pressure med. Pharmacist swapped his Amlodipine/HCTZ for a different brand - same drugs, different ratios. He ended up dizzy for two days. Never assume ‘same ingredients’ = ‘same pill.’

Always check the label. Always.

And yes, I’m filing a complaint. 😡

Kevin Wagner

November 13, 2025 AT 15:59THIS IS A DISASTER waiting to happen. Pharmacists are NOT doctors. They’re not trained to weigh complex drug interactions, and yet they’re being handed the keys to a patient’s life? The system is BROKEN. We need federal standards NOW - not state-by-state chaos. And stop pretending ‘cost savings’ justifies risking lives. This isn’t economics - it’s medical malpractice with a pharmacy stamp.

🔥

gent wood

November 14, 2025 AT 01:28I’ve worked in UK community pharmacy for 18 years, and we’ve had similar issues with FDCs - particularly with antihypertensives and antiretrovirals. The key difference? We have a national, clinically validated list of interchangeable combinations, and pharmacists are trained to consult it - not guess. We also have mandatory documentation for every substitution. It’s not perfect, but it’s far safer than the U.S. free-for-all.

Perhaps it’s time for a national database - with FDA oversight - to define what ‘therapeutically equivalent’ actually means for multi-drug products?

Dilip Patel

November 14, 2025 AT 20:41USA always mess up everything. In India we have combo pills for everything - TB, BP, diabetes - and pharmacists swap them daily. No one dies. Why? Because we trust our doctors and pharmacists. You Americans overthink everything. Just take the pill. If it works, good. If not, go back to doctor. Simple. No lawsuits. No Purple Book. No drama. 😎

Peter Aultman

November 16, 2025 AT 11:07My pharmacist just called me last month about my HIV med - switched me to a generic combo without telling me. I didn’t notice until I checked the pill color. I asked why. He said ‘it’s the same drugs.’ I said ‘but what if the release profile is different?’ He paused. Then said ‘I’ll call your doctor.’

Good call.

Turns out the generic had a delayed release. Not safe for me.

Lesson: always check. Always ask. Even if they say ‘it’s fine.’

Chris Ashley

November 17, 2025 AT 18:07Wait so you’re saying pharmacists can’t even swap a combo for a combo if the dosing is different? But what if the patient can’t afford the brand? Should they just go without? This system is literally killing people for profit. The FDA is asleep at the wheel. Someone needs to sue these boards.

And why is this even a question? It’s 2024.

kshitij pandey

November 18, 2025 AT 05:04As someone from India who moved to the US for med school - this is so confusing. Back home, combo pills are the norm. We don’t have 10 different pills for one condition. Here, it’s like a pharmacy puzzle. But I get it - safety matters. Maybe we need a color-coded system? Like green for simple combos, red for complex ones? And pharmacists should have to scan a QR code on the bottle to confirm substitution legality?

Just a thought.

Brittany C

November 18, 2025 AT 11:52From a clinical pharmacology perspective: the FDA’s Purple Book is woefully outdated for FDCs. Only ~12% of combination products have therapeutic equivalence ratings. Meanwhile, bioequivalence studies for combos are methodologically complex - you need to assess pharmacokinetics for each component, not just the sum. This isn’t just a legal gap - it’s a scientific one. Until we standardize PK/PD criteria for multi-drug products, substitution should be restricted to prescriber-initiated changes. Period.

Sean Evans

November 19, 2025 AT 03:58Oh please. ‘Patients are paying the price’? No. The price is being paid by the insurance companies and Big Pharma. You think they want you to pay less? They want you to pay MORE - because generics eat into their margins. The ‘safety’ argument is a smokescreen. They’d rather you take three pills for $200 than one for $30. And now they’re hiding behind ‘legal liability’ to keep prices high. Wake up. This isn’t about safety. It’s about greed.

💉💸

Brian Bell

November 21, 2025 AT 02:40My mom’s on a combo for bipolar. Switched pills last month. Thought it was the same. She had a panic attack. Turned out the new one had a different filler that triggered her anxiety. She’s fine now, but… wow. Just… wow.

Don’t ever assume. Ask. Always.

And if you’re a pharmacist? Call the doctor. Even if it takes 10 minutes. It’s worth it.