Prophylactic surgery is a pre‑emptive surgical approach designed to remove at‑risk tissue before cancer develops. In the context of hereditary polyposis syndromes, it offers a life‑saving shortcut around the long, uncertain road of endless polyp surveillance.

Understanding Polyposis Syndromes

Hereditary polyposis disorders are characterized by hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps lining the colon and sometimes the duodenum. The two most common genetic culprits are the Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and MUTYH‑associated polyposis (MAP). Both stem from germline mutations-APC for FAP and MUTYH for MAP-leading to uncontrolled cell growth.

The APC gene mutation is the classic driver: patients inherit one defective copy, and a second hit in the colon epithelium triggers polyp formation. By age 20, classic FAP patients often have over 100 polyps; MAP carriers usually develop a slightly lower burden but still face a steep cancer risk.

Without intervention, the cumulative lifetime risk of colorectal cancer in untreated FAP exceeds 90%. Duodenal adenomas are also common, adding a 4‑10% risk of duodenal cancer. These stark numbers make a compelling case for early, decisive action.

Why Prophylactic Surgery Becomes the Preferred Path

Surveillance colonoscopy can keep an eye on polyps, but the procedure is invasive, expensive, and plagued by missed lesions. Studies from major academic centers (e.g., the 2022 NCCN cohort) show that even with yearly scopes, interval cancers still emerge in 15‑20% of FAP patients after age 30.

Prophylactic surgery eliminates the primary source of malignant transformation. By removing the colon-or most of it-before any polyp becomes invasive, the surgery reduces colorectal cancer mortality to under 1% in long‑term follow‑up. The trade‑off is a permanent alteration of bowel anatomy, which must be weighed against the certainty of cancer avoidance.

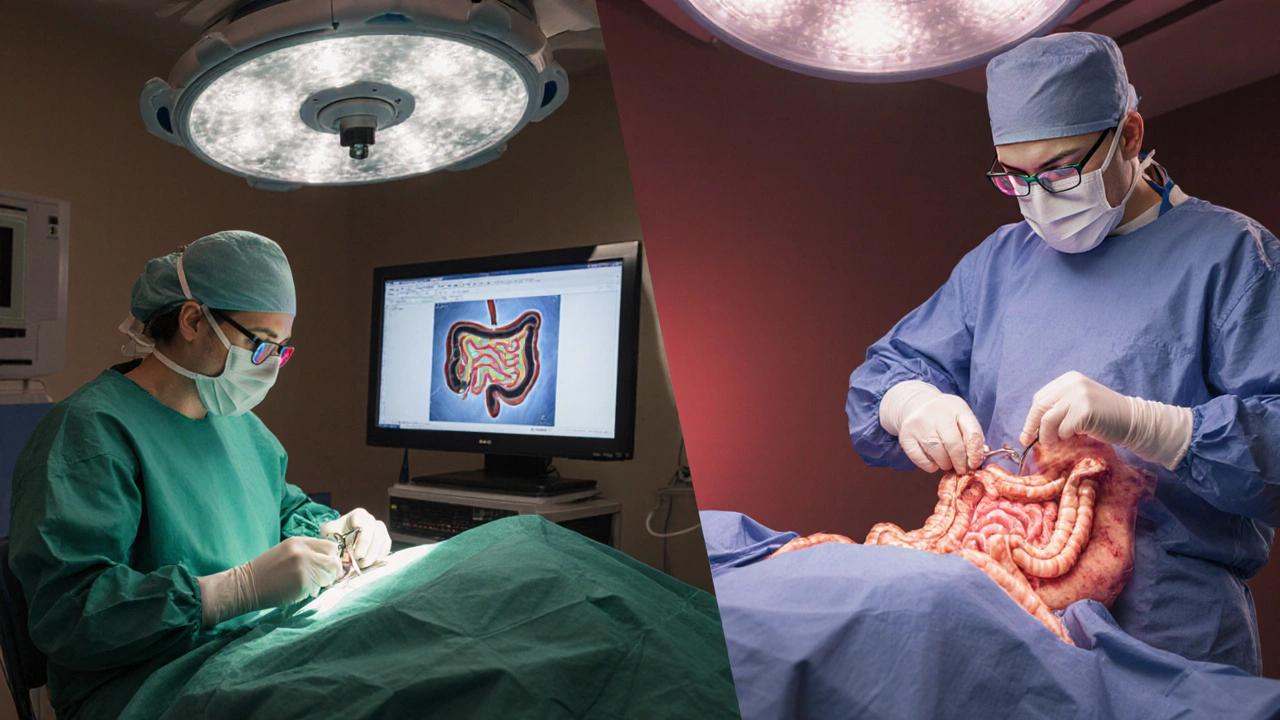

Surgical Options: A Side‑by‑Side Look

| Procedure | Extent of Resection | Rectal Preservation | Typical Indication | Post‑Op Function | Residual Cancer Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtotal Colectomy with Ileorectal Anastomosis (IRA) | Colon removed, rectum left intact | Yes | FAP patients with < 20cm of disease‑free rectum | More frequent stools, occasional urgency | 5‑10% (rectal polyp progression) |

| Total Proctocolectomy with Ileal Pouch‑Anal Anastomosis (IPAA) | Entire colon and rectum removed, J‑pouch created | No | Extensive rectal disease or high duodenal burden | 2‑3 bowel movements per day, night‑time urgency possible | <1% (pouch adenomas rare) |

| Segmental Resection | Only the most dysplastic segment removed | Yes | Localized high‑grade dysplasia, patient declines total surgery | Normal | 15‑20% (remaining colon at risk) |

Choosing between these paths hinges on three variables: polyp distribution, patient age, and the presence of extra‑colonic disease. The NCCN Guidelines recommend IRA for patients with a relatively disease‑free rectum and good compliance with endoscopic surveillance. IPAA becomes the default when the rectum harbors dense polyps or when a durable, cancer‑free pouch is preferred over lifelong rectal monitoring.

Decision‑Making Framework: From Genes to Goals

1. Genetic Confirmation: A definitive APC or MUTYH mutation test is the starting line. Without a confirmed diagnosis, prophylactic surgery risks overtreatment.

2. Polyp Burden Mapping: High‑resolution colonography and chromoendoscopy quantify both colon and rectal involvement. Duodenal staging (Spigelman score) adds another layer; a score >4 often tips the scale toward total proctocolectomy.

3. Age & Lifestyle Considerations: Younger patients (<25) who can tolerate a pouch tend to favor IPAA, while older adults may find IRA less disruptive to pelvic floor function.

4. Patient Preference: A shared decision‑making session that discusses stool frequency, sexual function, and the psychological impact of living with a permanent stoma (if needed) is essential.

5. Surgeon Expertise: High‑volume colorectal centers report a 30% lower complication rate for IPAA, underscoring the importance of seeking a surgeon with a proven track record.

Outcomes, Quality of Life, and Complications

Long‑term data from the European FAP Registry (2023) show that 85% of patients report a satisfactory quality of life after IPAA, compared with 78% after IRA. Common post‑op issues include pouchitis (≈20% of IPAA patients) and increased stool frequency. IRA patients face a higher probability of rectal polyp recurrence, necessitating lifelong endoscopic surveillance every 6-12months.

Complication rates differ markedly: IPAA carries a 5‑7% risk of anastomotic leak, while IRA has a 2‑3% leak rate. Both procedures share a ≤1% risk of peri‑operative mortality in experienced centers. Fertility concerns-particularly for women-are more pronounced after IPAA due to pelvic nerve manipulation; counseling with a reproductive specialist is recommended.

Post‑Surgical Surveillance: The Work Doesn’t End at the OR

Even after the colon is gone, the risk of duodenal adenomas persists. The Spigelman staging system guides endoscopic follow‑up: scores 0-2 merit surveillance every 5years, 3-4 every 2-3years, and ≥5 demand yearly duodenoscopy and consideration of prophylactic duodenectomy.

For patients with an IRA, the retained rectum requires colonoscopic checks at least annually. Emerging data suggest that topical NSAIDs (e.g., celecoxib) can slow rectal polyp growth, offering an adjunct to endoscopic removal.

In the pouch, routine pouchoscopy is not mandatory unless symptoms arise, but annual stool‑based DNA tests for dysplasia are gaining traction as a non‑invasive safeguard.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Minimally invasive techniques-laparoscopic and robotic‑assisted colectomies-have cut hospital stays from a week to 2‑3days, with comparable oncologic outcomes. Gene‑editing trials (CRISPR‑Cas9) targeting the APC mutation are still pre‑clinical, but they raise the possibility that prophylactic surgery could become optional for future generations.

Meanwhile, chemoprevention continues to evolve. A 2024 multi‑center trial showed that a combination of sulindac and erlotinib reduced duodenal polyp size by 35% in MAP patients, suggesting that drug therapy may delay or diminish the extent of required surgery.

Finally, patient‑reported outcome measures (PROMs) are being incorporated into clinical pathways, ensuring that decisions around prophylactic surgery align with individual life goals, not just statistical risk reductions.

Putting It All Together

Prophylactic surgery remains the most decisive weapon against colorectal cancer in polyposis syndromes. The choice between IRA and IPAA-or occasional segmental resection-must balance genetic risk, polyp distribution, patient age, and personal priorities. Close collaboration among gastroenterologists, genetic counselors, and high‑volume colorectal surgeons guarantees that the selected approach maximizes cancer protection while preserving the best possible quality of life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main goal of prophylactic surgery in polyposis?

The goal is to remove tissue that is almost certain to become cancerous, thereby dropping the lifetime colorectal cancer risk from over 90% to less than 1%.

When is an ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) preferred over an IPAA?

IRA is preferred when the rectum contains few or no polyps (typically <20cm disease‑free segment), the patient is older, and they are willing to undergo lifelong rectal surveillance.

How often should I undergo surveillance after an IRA?

Annual or semi‑annual flexible sigmoidoscopy is recommended to monitor the retained rectum for new polyps.

What are the most common complications after an IPAA?

Pouchitis (inflammation of the ileal pouch) occurs in roughly 20% of patients, and there is a 5‑7% risk of anastomotic leak during the early postoperative period.

Does prophylactic surgery eliminate the need for duodenal surveillance?

No. Patients with FAP or MAP still develop duodenal adenomas, so periodic duodenoscopy based on the Spigelman score remains essential.

Dana Sellers

September 27, 2025 AT 16:48If you’ve got a family history of polyps, you owe it to yourself and your kids to consider cutting out the risk before it cuts you down. Waiting around for colonoscopies is selfish when a decisive surgery can save lives. The moral choice is clear: act now, don’t gamble with cancer.

Damon Farnham

September 27, 2025 AT 18:11Indeed, the epidemiological data, when scrutinized with rigorous statistical methodology, unequivocally demonstrate that prophylactic colectomy, notwithstanding its invasiveness, furnishes an unparalleled reduction in oncogenic mortality; consequently, the hesitancy exhibited by certain clinicians borders on professional negligence, a lamentable affront to evidence‑based medicine.

Gary Tynes

September 27, 2025 AT 19:18Totally get it, surgery’s scary but it’s the best move for fams with FAP.

Marsha Saminathan

September 27, 2025 AT 20:16When I first heard about prophylactic surgery for polyposis, my mind raced through a kaleidoscope of emotions. I imagined a life liberated from the relentless calendar of colonoscopies. I pictured the freedom of eating a slice of pizza without the gnawing dread of hidden polyps. The statistics, though stark, felt like a compass pointing toward decisive action. A 90% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer is not a suggestion; it is a thunderclap demanding response. Removing the colon before cancer can take root is akin to pulling the weeds before they choke a garden. Patients who undergo a subtotal colectomy often report a handful of extra trips to the bathroom, a small price for peace of mind. The alternative-endless surveillance-drains both wallets and nerves, a slow‑burn catastrophe. Surgeons, armed with modern techniques, can create an ileal pouch that mimics natural function remarkably well. Even the occasional night‑time urgency pales in comparison to the certainty of surviving past 40 without a tumor. From a psychological standpoint, taking control of one’s destiny can spark a renaissance of confidence. Families see a generational shift as the fear that once hovered like a specter fades into a distant memory. Medical teams, too, find solace in knowing they have offered a definitive solution rather than perpetuating a gamble. Critics who cling to the “watchful waiting” mantra often underestimate the emotional toll of living under a microscope. In the grand tapestry of preventive medicine, prophylactic surgery stands out as a bold, vibrant thread. So, if you carry the APC mutation, consider the surgery not as a loss but as a powerful gift to yourself and the ones you love.

Justin Park

September 27, 2025 AT 21:06Interesting read! 🤔 The balance between surgical risk and cancer prevention is a classic ethical dilemma, and the data you referenced really highlight the stakes. I’d add that patient preference surveys consistently show a willingness to accept higher stool frequency for a near‑certain cure.

Herman Rochelle

September 27, 2025 AT 21:48I appreciate the thorough overview, especially the clear breakdown of IRA versus IPAA. This helps patients make informed choices without getting lost in medical jargon.

Stanley Platt

September 27, 2025 AT 22:21Your exposition, esteemed colleague, delineates the surgical alternatives with commendable precision; the inclusion of quantitative risk assessments, such as the 5‑10% residual rectal cancer incidence post‑IRA, enhances clinical decision‑making considerably. 😊

Alice Settineri

September 27, 2025 AT 22:46Whoa, that was a poetic ride! 🎉 I love how you painted the surgery as a garden‑tending act-totally got me visualizing the weeds being yanked out.

nathaniel stewart

September 27, 2025 AT 23:06Your summary is quite informative; I wholeheartedly endorse the notion that early prophylactic colectomy can dramatically uplift life expectancy, despite the minor typoes.

Pathan Jahidkhan

September 27, 2025 AT 23:25Life is a fleeting script, surgery a bold edit that rewrites the tragedy of cancer into a hopeful sequel.

Dustin Hardage

September 27, 2025 AT 23:41From a surgical perspective, the decision algorithm should incorporate patient age, polyp burden, and duodenal involvement; recent guidelines suggest total proctocolectomy for rectal disease exceeding 20 cm, aligning with the data presented.

Dawson Turcott

September 27, 2025 AT 23:56Sure, because who doesn’t love a permanent J‑pouch and midnight bathroom trips? 😒 It’s the dream, right?

Alex Jhonson

September 28, 2025 AT 00:10I think it’s crucial we respect each individual’s cultural view on surgery; many communities see the ileal pouch as a bridge between tradition and modern medicine.

Katheryn Cochrane

September 28, 2025 AT 00:21The article glosses over the psychological burden; it’s not all sunshine and rainbows when you’re forced into a lifelong bowel routine.

Michael Coakley

September 28, 2025 AT 00:31Oh great, another reason to add more meds to the list, because we needed that.

ADETUNJI ADEPOJU

September 28, 2025 AT 00:40In the realm of preventative oncology, it is the unequivocal duty of clinicians to propagate prophylactic resection as the gold standard, lest we indulge in antiquated surveillance inertia.

Janae Johnson

September 28, 2025 AT 00:46While the consensus leans toward early surgery, I maintain that a subset of patients may benefit from a more conservative, watchful approach, defying the prevailing narrative.

Kayla Charles

September 28, 2025 AT 00:51Your comprehensive table is a treasure trove for anyone navigating the maze of surgical options; each procedure’s nuances are laid out with clarity that empowers both physicians and patients alike. The inclusion of functional outcomes alongside residual cancer risk offers a holistic perspective often missing in brief reviews. I encourage readers to discuss these findings with their multidisciplinary team to tailor the best individualized plan. Moreover, sharing personal anecdotes about postoperative quality of life can further demystify the decision‑making process. Ultimately, knowledge is the catalyst that transforms fear into informed confidence.

Paul Hill II

September 28, 2025 AT 00:55Great summary, balanced and neutral, that captures the key points without overstating any single option.