Ever wonder why some drugs have two names? You might see acetaminophen on a bottle in the U.S., but paracetamol on the same pill sold in Europe. Or why albuterol is in your inhaler, but your doctor from another country calls it salbutamol. These aren’t typos. They’re the result of two global systems that decide what drugs are called before they ever hit the shelf: USAN and INN. And behind them? A whole process that shapes how medicines are named - and why some names stick while others get tossed out.

What Are USAN and INN?

USAN stands for United States Adopted Names. It’s the official system used in the U.S. to give nonproprietary names to drugs. Think of it as the government’s way of making sure every drug has one clear, standardized name doctors and pharmacists can trust. The USAN Council, made up of experts from the American Medical Association, the U.S. Pharmacopeia, and the American Pharmacists Association, manages it. They’ve been doing this since 1964.

INN, or International Nonproprietary Name, is the global version. Run by the World Health Organization since 1950, INN gives drugs the same name across nearly every country. That’s why you’ll see omeprazole on a label in Japan, Brazil, or Germany - same name, same drug.

The big goal? Safety. If a doctor in New York writes a prescription for clindamycin, and a pharmacist in Sydney reads it, they both know exactly what drug is meant. No confusion. No mix-ups. That’s the whole point.

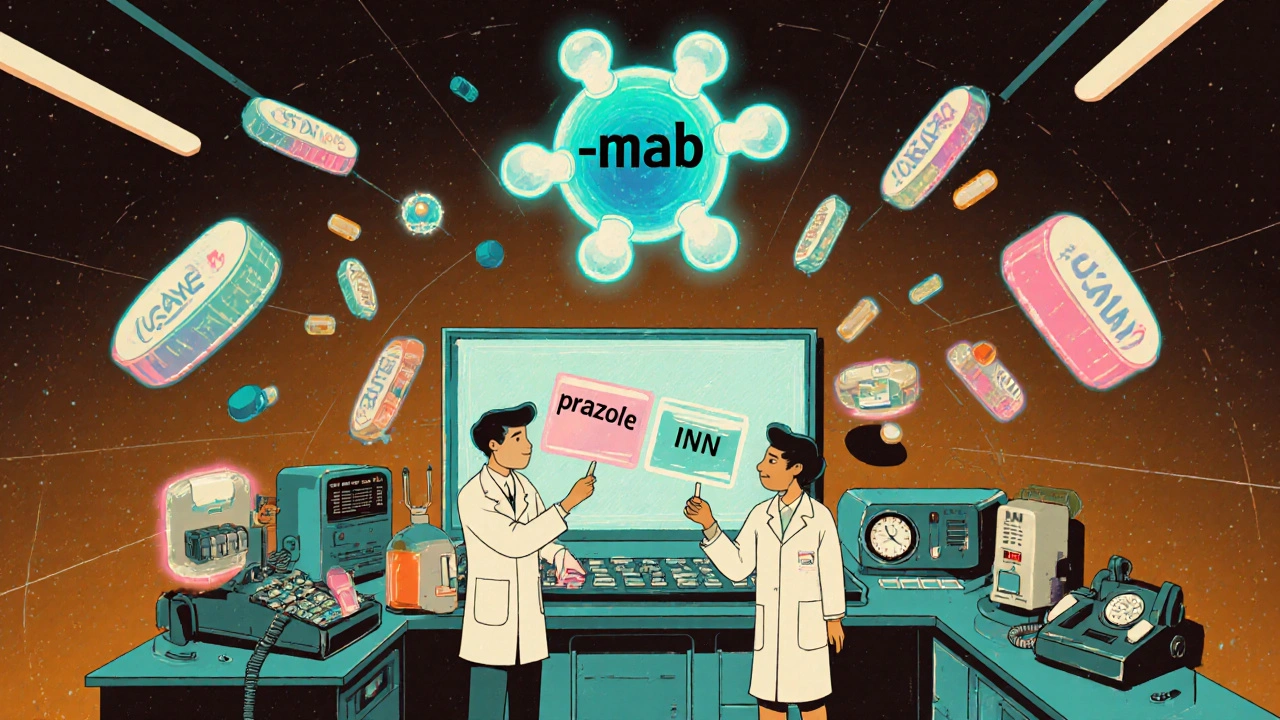

How Do These Names Work? The Stem System

Here’s where it gets clever. Both USAN and INN don’t just make up random names. They use a system built on stems - endings that tell you what the drug does.

Take -mab. If a drug ends in -mab, it’s a monoclonal antibody. That’s a type of biologic drug used to treat cancer, autoimmune diseases, and more. But it doesn’t stop there. If it ends in -ximab, like rituximab, it’s a chimeric antibody (part mouse, part human). If it ends in -zumab, like adalimumab, it’s humanized (mostly human). That’s instant classification.

Other common stems:

- -prazole - proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, esomeprazole)

- -statin - cholesterol-lowering drugs (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin)

- -feron - interferons (interferon alfa-2a)

- -virdine - HIV drugs (efavirenz, lamivudine)

The beginning of the name - the part before the stem - is usually a made-up, catchy syllable. It’s not random. It’s designed to sound smooth, avoid sounding like other drugs, and not accidentally mean something weird in another language. For example, esomeprazole isn’t just omeprazole with an ‘e’ slapped on. The ‘es-’ tells you it’s a specific version - the S-isomer - of the original molecule. That’s chemistry in a name.

Why Do We Have Two Systems? USAN vs. INN

Here’s the twist: USAN and INN are almost the same - but not quite. About 95% of the time, they match. But there are a few stubborn differences.

Some of the most common mismatches:

- Acetaminophen (USAN) vs. Paracetamol (INN)

- Albuterol (USAN) vs. Salbutamol (INN)

- Rifampin (USAN) vs. Rifampicin (INN)

Why do these exist? History. The U.S. had its own naming practices before INN became widespread. When the WHO pushed for global standardization, the U.S. didn’t fully abandon its own terms. So now we have two names for the same drug - and that’s where problems start.

There have been real cases where patients got the wrong dose because a nurse saw salbutamol on a European label but thought it was a different drug than albuterol. The FDA doesn’t require INN names on U.S. labels - only USAN. But international travelers, imported medications, and global clinical trials can get messy.

USAN’s advantage? It’s tailored to U.S. medical culture. INN’s advantage? It’s truly global. The trade-off is a small but dangerous gap in clarity.

How a Drug Gets Its Name - The Long Road

Getting a name isn’t quick. It doesn’t happen when the drug is ready to sell. It happens early - often during Phase 1 or 2 clinical trials. That’s because the naming process takes 18 to 24 months.

Here’s how it works:

- A drug company picks 5-6 potential names. They hire specialists to check for conflicts - not just with other drugs, but with brand names, slang terms, or even words that sound like insults in other languages.

- They submit these names to both USAN and INN. The USAN Council reviews them, checks databases, and may suggest alternatives. About 30-40% of submissions need multiple rounds because of conflicts.

- Once USAN approves a name, it goes to WHO’s INN team. They either accept it or propose a different version.

- After approval, the name is published. There’s a 4-month window for public objections. If no one objects - which almost never happens - the name is official.

And here’s the kicker: about 65% of drugs that get a USAN name never make it to market. Clinical trials fail. Safety issues pop up. But the name stays in the system - available for future use.

Brand Names vs. Generic Names

Don’t confuse the generic name with the brand name. Atorvastatin is the generic. Lipitor is the brand. The generic name is public domain - anyone can use it. The brand name is trademarked. Pfizer owns Lipitor. No one else can use it.

Brand names are marketing tools. They’re catchy, easy to remember, and often tied to the drug’s benefit. Viagra sounds like vigor. Prozac sounds calming. But they’re not regulated like generic names. No stems. No rules. Just creativity - and legal teams.

That’s why you’ll see the same generic drug sold under different brand names: ibuprofen is sold as Advil, Motrin, Nuprin, and dozens of others. The generic name stays the same. The brand name changes.

What’s Changing in Drug Naming?

The old stem system was built for pills and injections. Now we have gene therapies, RNA drugs, and antibody-drug conjugates. These don’t fit neatly into -mab or -prazole.

WHO updated its monoclonal antibody naming rules in 2021 to handle newer types - like bispecific antibodies and Fc-engineered versions. USAN is working on similar updates. But it’s slow. Naming is conservative by design. You don’t want to change a system that keeps patients safe.

Still, pressure is growing. Biologics now make up 42% of global drug sales - over $380 billion in 2023. More complex drugs mean more naming challenges. Experts agree: the system works - but it’s being tested.

Why This Matters to You

If you take medication, you’re already using this system. When your pharmacist says, “This is the generic version of your brand drug,” they’re using the USAN or INN name. It’s the only way they know what’s in the pill.

And if you’re traveling? Know your drug’s INN name. If you’re prescribed albuterol in the U.S., ask for salbutamol abroad. It’s the same drug - just a different name.

Medication errors from confusing drug names cost the U.S. healthcare system about $2.4 billion a year. That’s not just money. It’s preventable harm. That’s why these naming rules exist - not for bureaucracy, but to keep you safe.

Final Thoughts

Generic drug names aren’t just labels. They’re coded messages. They tell you what the drug is, how it works, and how it’s related to others. USAN and INN are quiet heroes of modern medicine - invisible systems that make sure the right drug reaches the right person, every time.

And while brand names grab headlines, it’s the generic name that keeps the system running. The next time you see a long, odd-looking word on your prescription - remember: it’s not random. It’s science in a name.

Edward Ward

November 15, 2025 AT 15:03Okay, so I’ve been thinking about this for weeks now-like, really deep-dive, late-night-scrolling kind of thinking-and it’s wild how much we take these drug names for granted. I mean, you just see ‘acetaminophen’ on a bottle and think, ‘cool, painkiller,’ but behind that word is a whole committee of pharmacologists, linguists, and FDA bureaucrats arguing over syllables for months. And the stem system? Genius. It’s like a secret code only doctors and pharmacists know, but it’s literally saving lives by preventing mix-ups. I once saw a nurse panic because she thought ‘salbutamol’ was something new, not realizing it was just the international name for albuterol. That’s not a typo-that’s a systemic failure waiting to happen. And why does the U.S. still cling to ‘rifampin’ when the whole world uses ‘rifampicin’? Tradition? National pride? Either way, it’s a tiny, dangerous inconsistency in an otherwise brilliant system.

Andrew Eppich

November 15, 2025 AT 16:52It is deeply concerning that the United States continues to deviate from internationally recognized nomenclature. Such deviations are not merely semantic; they are a breach of professional responsibility. The World Health Organization established INN precisely to eliminate ambiguity in medical practice. To persist with USAN variants is to prioritize parochialism over patient safety. This is not a matter of preference-it is a matter of ethics. One would hope that American medical institutions would lead by example, not cling to outdated nationalistic conventions.

Jessica Chambers

November 17, 2025 AT 14:44So let me get this straight… we have a global system that works perfectly fine, but the US is like ‘nah, we’ll just make our own version, it’s cooler’? 😒

Also, ‘rifampin’ vs ‘rifampicin’? That’s not a difference, that’s a typo waiting to kill someone. 🤦♀️

Shyamal Spadoni

November 18, 2025 AT 15:04you know what this is really about? the pharmas and the govts are in cahoots to keep us confused so we dont realize how much theyre overcharging. why does acetaminophen cost 10x more than paracetamol? same exact molecule. same exact science. but if you call it something different, you can sell it as a new product. they even make the names look different on purpose. its all a scam. and the stems? theyre just to make you think its science when its just marketing with a lab coat. they dont want you to know its the same drug. they want you to think you need a new one every time. watch this video on youtube: ‘drug naming conspiracy’ its got 2 million views and nobody talks about it

Ogonna Igbo

November 19, 2025 AT 01:41Why does America think it’s above global standards? This is not about tradition-it’s about arrogance. Nigeria uses INN. India uses INN. Brazil uses INN. But the U.S. still clings to ‘albuterol’ like it’s a cultural trophy? You want to be a global leader in medicine? Then stop being a linguistic island. Your patients are dying because nurses don’t know if ‘rifampin’ is different from ‘rifampicin.’ You call that innovation? That’s negligence dressed up as patriotism. The world doesn’t care about your USAN. It cares about safety. And we’re all paying the price for your stubbornness.

BABA SABKA

November 20, 2025 AT 01:45Stem systems are the only reason I didn’t get prescribed the wrong drug last year. I’m a med student in Lagos, and I’ve seen people get dosed wrong because they mixed up ‘omeprazole’ with ‘omeprazol’ (someone spelled it wrong on a handwritten script). But the stem? -prazole? That’s your lifeline. You see it, you know it’s a PPI. No guessing. No panic. Even if the first part of the name is some corporate buzzword like ‘es-’ for esomeprazole, the stem tells you the mechanism. That’s why I’m not surprised biologics are breaking the system-those drugs are so complex, they need new stems. But the FDA’s slow? Of course. They’re still arguing over whether ‘-mab’ should be ‘-mab’ or ‘-mabv’ for bispecifics. Meanwhile, patients in Lagos are getting real meds with real names. The system works. It just needs to evolve faster than American bureaucracy.

Chris Bryan

November 20, 2025 AT 09:09INN is a WHO plot. They want to control American medicine. Who gave them the right to dictate how we name our drugs? The USAN Council is made of real doctors-experts who know American clinical practice. The WHO? A bunch of bureaucrats in Geneva who’ve never held a stethoscope. Why should I trust a name that’s decided by someone in Sweden who doesn’t even know what a 72-year-old diabetic with renal failure needs? They changed ‘rifampin’ to ‘rifampicin’ because they thought it sounded ‘more European.’ That’s not science. That’s cultural imperialism. And now our kids are learning two names for the same drug in school. This isn’t standardization-it’s erasure.

ASHISH TURAN

November 21, 2025 AT 02:48Interesting how the stem system works like a language. It’s not just about classification-it’s about communication across cultures. I grew up in India where we used INN names, but my uncle worked in a U.S. hospital and kept mixing up ‘albuterol’ and ‘salbutamol.’ He thought they were different drugs. Took him three years to realize they were the same. The real problem isn’t the names-it’s the lack of education. If every pharmacist and nurse understood the stem system, we wouldn’t need to force global uniformity. Just teach the code. The names will follow.

Ryan Airey

November 21, 2025 AT 09:54Let’s be real-this entire system is a glorified corporate tax dodge. The ‘USAN vs INN’ debate is a distraction. The real issue? Pharma companies spend millions to get a name that sounds like it’s ‘new’ and ‘patentable’-even if it’s the same damn molecule. ‘Esomeprazole’? That’s just the S-isomer of omeprazole. They didn’t invent anything. They just isolated one half of the molecule and called it a ‘breakthrough.’ Then they charged 300% more. The stems? Cute. But the naming process? A shell game designed to keep generics from competing. You think ‘-mab’ tells you it’s a monoclonal antibody? Yeah. But it doesn’t tell you it’s a $50,000-a-year drug. That’s the real story.

Hollis Hollywood

November 22, 2025 AT 10:12I just want to say how much I appreciate this post. I’m a pharmacy tech, and I’ve seen firsthand how confusing it is when patients come in with prescriptions from abroad. One elderly woman brought in a bottle labeled ‘paracetamol’ and insisted it was ‘not the same’ as the Tylenol she’d been taking for 20 years. It took me 20 minutes to explain that it was literally the same pill, just a different name. I wish more people knew about stems. I wish more doctors explained them. It’s not just about safety-it’s about trust. When patients understand that ‘-statin’ means cholesterol, they feel more in control. And that matters. This system isn’t perfect, but it’s one of the few things in medicine that actually tries to put the patient first, even if it’s buried under bureaucracy.

Aidan McCord-Amasis

November 23, 2025 AT 17:28albuterol = salbutamol 😴

acetaminophen = paracetamol 🤷♂️

why are we still doing this? 🤦♂️

Adam Dille

November 25, 2025 AT 08:56bro i just found out that ‘-virdine’ means it’s an HIV drug and now i’m obsessed. like, i’m looking at my meds and going ‘ohhh that’s a -prazole!’ 🤯

also, ‘esomeprazole’ sounds like a Marvel villain. ‘I am Esomeprazole… and i neutralize your stomach acid!’ 😂

thanks for making drug names actually cool.

Katie Baker

November 26, 2025 AT 20:38This is actually so cool! I never realized how much thought goes into naming drugs. I just thought they picked random words. Now I’m looking at my prescription like it’s a secret code-and it kind of is! 😊

Also, I’m gonna tell my grandma that ‘paracetamol’ and ‘acetaminophen’ are the same thing. She’s been convinced they’re different since 2003. Time to set her straight!